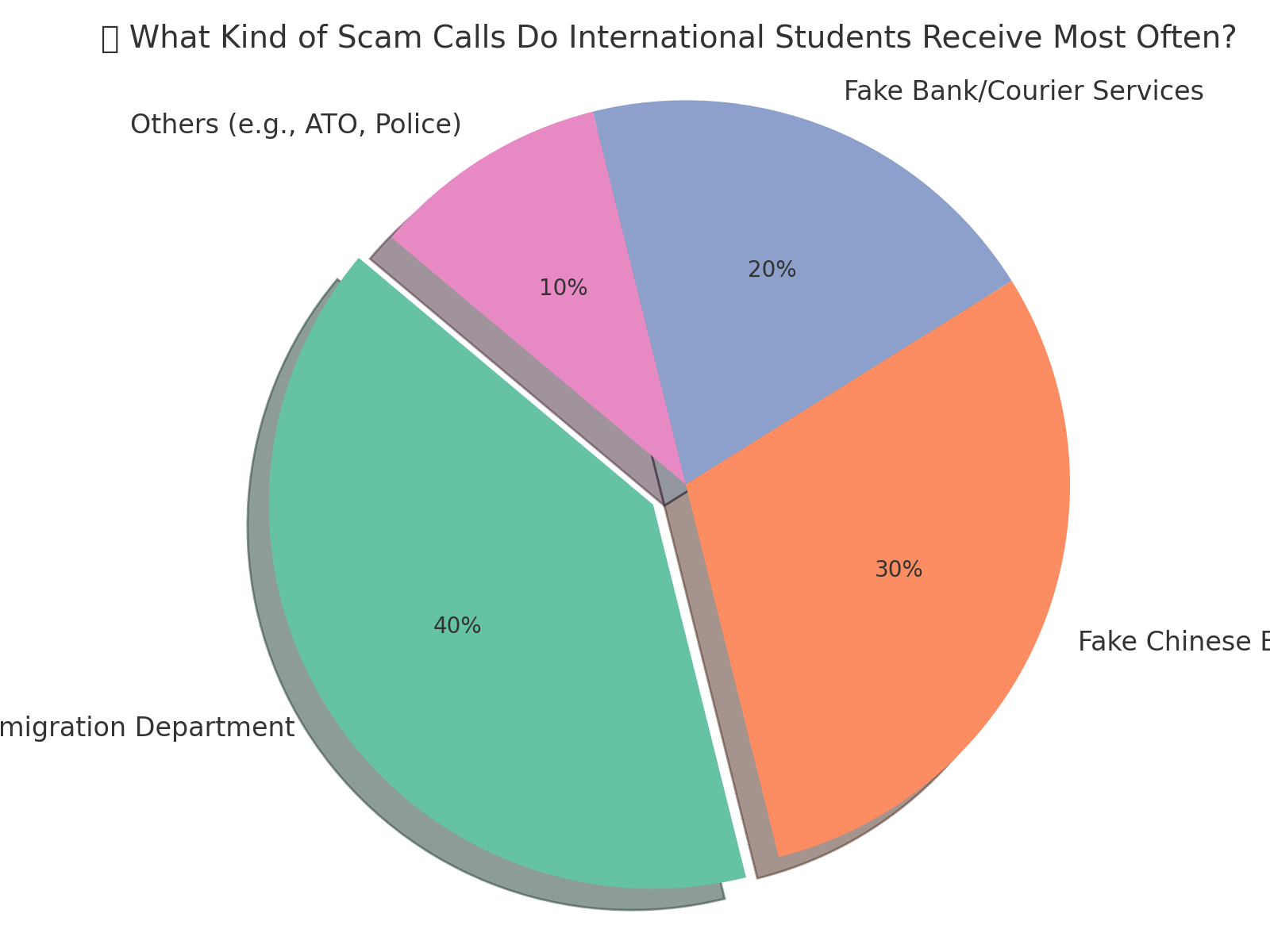

Have you ever received a call from the “Visa Center” or the “Immigration Bureau”? Or maybe someone claimed your phone number is about to be suspended?

What seemed like an official warning may have been the start of a sophisticated scam—one that’s increasingly targeting international students in Australia.

A strange and dangerous call

In February, when Ziming Wang arrived in Sydney from China to study international law at the University of Sydney, he was excited to learn a totally new major in a new country. What he didn’t expect was to become a victim of an online scam, which made him lose $2000.

“I got a call saying it was from the Australian Immigration Department,” Wang recalls. “They said my name, my address, my date of birth, even my visa information. It makes me not doubt them anymore.

What followed was a high-pressure situation, Wang was told that his bank had been used illegal and he was suspected of involvement in a criminal case. The scammer urged him to click on a link to an “official” government website and warned that the consequences of uncooperation could be severe.

“I couldn’t think at that time, I was totally freaked,” he says, “They even let me report my activities once per hour. I just did what they told me.”

A growing and targeted threat

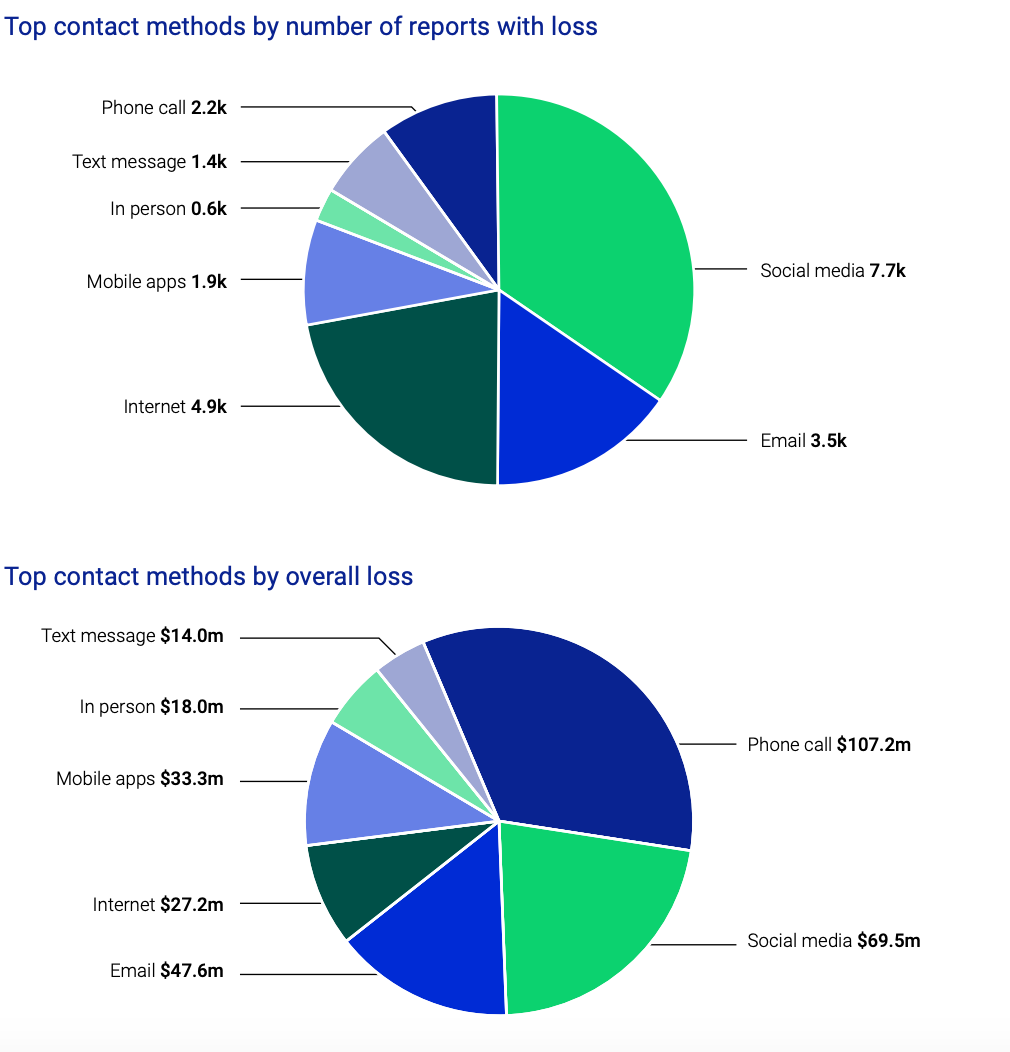

Wang’s experience is not one of the minority. According to the National Anti-Scam Centre’s most recent Targeting Scams report, Australians lost more than $2 billion to scams in 2024, with international students emerging as one of the most vulnerable demographics.

“These scams are often tailored to exploit cultural and linguistic gaps,” Dr Jacqueline Drew, Associate Professor at Griffith University’s School of Criminology, said to ABC News, “They target people who are unfamiliar with Australia’s systems and who might hesitate to seek help due to fear or shame.”

Dr Drew has conducted extensive interviews with scam victims. All of them have one consistent feeling, a gut feeling that something was wrong.

The manipulation of the scam

Scammers commonly use various psychological tactics, such as creating fear and pretending to be authority figures, to manipulate victims. These strategies exploit emotional vulnerabilities, making them particularly effective against international students who may be unfamiliar with local customs and regulations.

“In my case, the website, which the scammer eand to me, looked exactly like the Immigration Department’s,” Wang says. “They even had an online chatbot. It was only later that I realised it was all fake.”

The emotional distress, he says, was as heavy as the financial loss.

“I didn’t tell my parents for weeks, I feel ashamed and stupid. I thought they would be disappointed.”

And Wang’s case is just one among thousands. The numbers speak for themselves.

From potential victim to protector

Not everyone fell into the scam trap. Jie Guo, a science master’s student also studying at the University of Sydney, says she was almost there.

“I got a call from someone claiming to be from the Chinese Consulate. They said I was involved in a cross-border crime. It sounded ridiculous—but also serious,” she says.

Guo didn’t hand over any money, but the encounter made her alert. A week later, a classmate casually mentioned she was about to transfer thousands of dollars to “clear her record.” Guo stopped her in time.

“She was shaking. The scammer told her not to talk to anyone about her situation. They even monitored her through a video call.”

Guo believes awareness is the first line of defence. “We need to talk to each other, it really helps to know you’re not alone.”

Why are students vulnerable?

Yilin Wang, a PhD candidate at the University of Wollongong, points that a mixture of cultural, emotional, and practical vulnerabilities makes the international students target.

“When you first arrive in a new country, you need to deal with a new language, a new environment, and new rules. You don’t know whether to trust others,” she says. “If someone says you’ve broken the law, your instinct is to compromise, not to question.”

She also notes that many international students are hesitant to report scams due to shame or fear of academic or visa consequences.

According to the National Anti-Scam Centre’s Targeting Scams Report (March 2025), threat-based scams resulted in the highest total losses among those aged 18 to 24. The report attributes this in part to the high volume of both real and fake sextortion scams, as well as authority scams that specifically target young migrants and international students.

The silence that helps scammers

According to a January 2025 study by the Commonwealth Bank, more than 60% of Australians say they’re more worried about scams now than in 2024. However, only 8% would feel comfortable discussing it with family or friends.

James Roberts, Head of Group Fraud at the Commonwealth Bank, says that silence is the scammers’ greatest ally.

“Talking about scams is key to breaking the cycle,” he said in a CBA Newsroom statement. “Share your experiences. Warn others. You’re not weak—you’re helping.”

Beyond personal responsibility

Dr Drew emphasises that stopping scams is not just an individual’s responsibility.

“Financial institutions, telecommunications providers, and social media platforms all play a role,” she says. “Blocking known scam numbers, improving user warnings, and educating vulnerable groups must be a coordinated effort.”

Several Australian universities have also launched study modules and workshops focused on scam prevention, often in collaboration with the police and anti-fraud experts.

If you or someone you know has been affected by a scam, you can report it at www.scamwatch.gov.au or call 1300 795 995. Support is also available through government services, community organisations, and university student support centres.

If you’ve experienced a scam—or narrowly avoided one—we’d like to hear from you. Share your story in the comments below. Your voice could help protect others!

Be the first to comment