In Burwood, Sydney, Yolanda Tan, a PhD student at the University of Sydney, is currently browsing her tenth rental application this month. Since 2020, she has moved house five times—not by choice, but because of rising rents or sudden landlord demands.

Photo: Kate Huang

“I had hoped Labor’s housing policies would consider the difficulties renters face,” she says. “But it doesn’t really feel like they have.”

Yolanda’s story is far from unique. In the years since COVID-19, Sydney’s rental market has become one of the most pressing social challenges in Australia.

The new housing policies of the Labour government seem to have forgotten about renters who are still in the midst of a turbulent rental market. Renters struggling to survive in the post-COVID era will also need the protection of more targeted policies.

A Rental Market Still Bleeding After COVID-19

The COVID-19 hit Australia’s rental market harder than anyone expected. While emergency measures like JobKeeper and eviction moratoriums eased short-term pressure, governments failed to plan for the long-term fallout.

Post-COVID era, immigration resumed and international students returned in large numbers. Between 2022 and 2023, Sydney’s population grew by 146,700—a 2.8% increase and one of the largest annual jumps in recent memory.

This rapid growth met a market with low housing supply, pushing rents sharply higher.

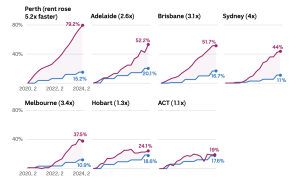

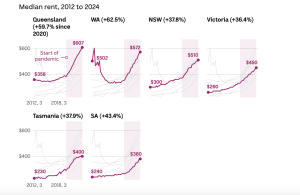

- +36.1% rent increase in Sydney since 2020 (CoreLogic)

-

Rent rising 5 times faster than wages in capital cities (SGS Economics)

-

Outer suburbs saw rent rise 35–65%, pushing low-income renters even further out (SGS Economics)

Source: ABC News / SGS Economics and Planning

For renters like Yolanda, who need stable housing to continue studying and working, soaring rents leave little choice.

“I wouldn’t say landlords are greedy,” she reflects. “It’s more about a broken system.”

As scholar Widmaier argues, one of the functions of crisis narratives is to push policy reform. In that sense—and in many others—the COVID-19 crisis is far from over.

Labor’s Housing Vision: Ambitious for Buyers, Unclear for Renters

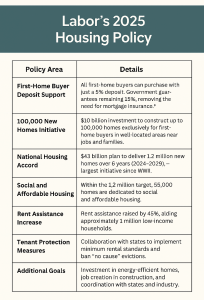

In 2025, the re-elected Labor government expanded its First Home Guarantee Scheme. All first-home buyers can now access the scheme with just a 5% deposit. Labor also pledged $10 billion to build 100,000 homes for first-home buyers.

The policy has been praised as a lifeline for aspiring homeowners.

But for renters—especially those locked out of the housing market by high prices—the benefits are far less clear.

-

Fairness Missing: Renters Remain Invisible

Sydney’s housing problem is not just about home ownership. Australia’s homeownership rate has been declining for decades—currently sitting around 66%, while roughly 31% of households rent.

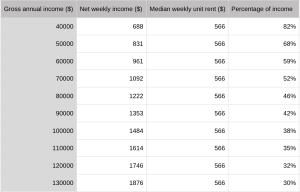

These renters also face having to spend up to half of their wages on rent. A new report by campaign group Everybody’s Home found that in areas such as Sydney, middle- and high-income earners face housing costs of more than 30% of their income. Those on low incomes can spend more than 70% of their salary on rent. The plight of renters in the face of rising rents and increasing difficulty in finding accommodation should also be recognised.

Source:Everybody’s Home Report

Labor’s policies also exclude many by design—low-income earners, migrants, and international students. In countries and cities where there are so many renters and so much pressure to rent, policies are focused almost exclusively on ownership rather than occupancy.

“As a PhD student, I can’t access the first-home scheme because my visa status is temporary,” Yolanda explains. “We’re part of Sydney’s economy, but we’re treated as disposable tenants.”

-

Timing Mismatch: Long-Term Plans Can’t Solve Short-Term Crisis

Labor’s policies are ambitious—5% deposits and 100,000 new homes—but they face significant delays. According to the NSW Government, Greater Sydney is projected to add 172,900 homes by 2028–29, averaging 28,800 per year. However, most of these homes are expected to be for ownership, not rental.

Source:NSW Government

Photo: Kate Huang

Sydney’s rental crisis is a now problem, not one that can wait three to ten years for structural interventions to take effect. Without immediate solutions, increased demand from buyer incentives may push prices even higher. Renters, in turn, will continue to bear the consequences.

Coordinated Policy Needed for a Post-COVID Rental Crisis

The truth is that Sydney’s rental market is still in crisis. In January 2025, Rent.com.au reported that the median weekly rent for a flat in Sydney had reached $720, one of the highest levels in the country.

In addition to high property prices, other rights of renters are not reasonably protected. An Instagram search for #RentersRights reveals hundreds of posts expressing dissatisfaction with renting – rising rents, poor maintenance, forced evictions.

As scholars have advised in post-pandemic research, to address the long-term rental problem, cross-sectoral collaboration needs to be promoted to systematically enhance the stability and fairness of the housing security and rental system.

The governments need to look beyond ownership and take renters seriously. That means linking housing policy with how people live and move today, by:

-

Connecting rental support to migration and population growth

-

Making rent part of urban planning and infrastructure decisions

-

Setting rent affordability limits to avoid financial stress

-

Tying immigration levels to the building of affordable homes

-

Letting local councils step in with temporary rent controls when needed

Post-pandemic recovery isn’t just about economic numbers. It’s about whether a PhD student can complete her research in between running around looking at houses, or if a new immigrant can afford to eat fresh fruit and veg even after paying rent. We need a housing system that supports buyers and renters alike—because a strong city is one that shelters everyone who helps build it.

Be the first to comment