After the 2025 Australian federal election, the Coalition lost the election and the Labor Party continued to govern. During the election campaign, the policy on international students became one of the hot topics. Although there are more than one reason for the Coalition’s defeat, its policy of “limiting the number of international students to ease housing pressure” has aroused strong social concern. The policy is seen as the Coalition’s response to the public’s anxiety in the context of high housing prices and tight rental conditions. Today, the ruling Labor Party is unable to shake the “cash cow” of education exports, but needs to face up to the public’s dissatisfaction with housing shortages. In this policy game, how the Labor Party chooses will become a realistic test of its ability to govern.

Are International Students Being Scapegoated Amid Australia’s Housing Crisis?

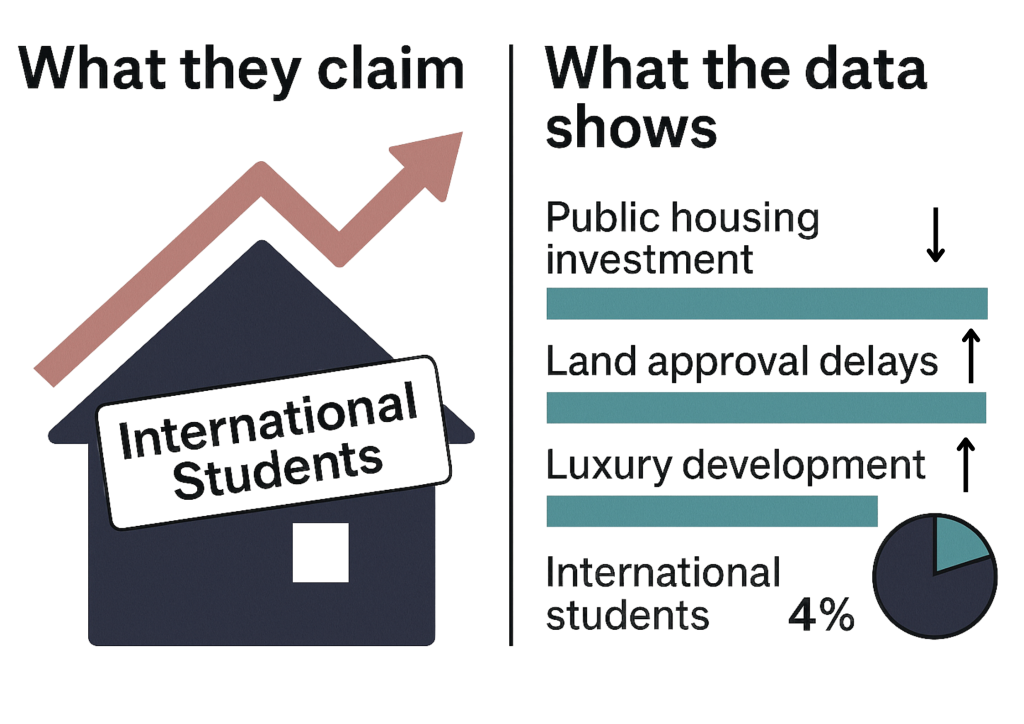

The Liberal Coalition pointed the finger at population growth from abroad, particularly the “surge” in international students, claiming it was a major driver behind skyrocketing property prices and rental shortages. Their proposed solution was to reduce student visa numbers in order to “free up space” and ease housing pressure. While this logic may appear straightforward and offer a quick response, thereby winning support from some voters, it ultimately fails to address the root causes of the housing crisis and is, at best, a superficial fix.

According to a 2024 study by the University of South Australia, there is no direct link between the increase in international students and rising rental prices. The study identified the real causes of housing stress as chronic underinvestment in public housing, inefficiencies in land approval and building permits at the local government level, and a private development sector focused on high-profit projects—factors that have led to a persistent shortage of affordable housing. The Student Accommodation Council also noted that international students account for only about 4% of the national rental market and are mainly concentrated in on-campus housing or student apartments, making their overall impact on the housing market minimal.

In reality, international students make significant contributions to Australia. They pay high tuition fees, and the resulting $50.5 billion in revenue doesn’t appear out of thin air.

Using international students as scapegoats does nothing to solve the housing crisis. Worse still, it risks damaging Australia’s international reputation in education and its commitment to diversity—not to mention the very real $50.5 billion in income. To truly resolve the housing issue, we must confront its systemic roots rather than shifting the blame to vulnerable members of a mobile population.

Labor’s dilemma: fiscal reality and public anxiety intertwined

After experiencing the financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, major universities are more dependent on tuition fees from international students to maintain teaching operations, scientific research funding and employee salaries. For USYD, international student tuition fees are 44% of its total annual revenue. If the federal government further tightens visa quotas, my calculations show that if the USYD’s international student numbers fall by 25 per cent, its annual revenue could fall by around A$900 million.

However, under the pressure of housing public opinion that continues to ferment after the election, the Labor government faces an obvious dilemma. The Labor Party seems to have chosen a compromise path. There is no clear plan to further reduce the number of international students to avoid a direct impact on the education sector, but the Labor Party uses technical means to control and increase visa application fees.

This balancing strategy is not a long-term solution. If the structural problems in the housing market are not effectively addressed, public dissatisfaction will continue to accumulate, and international education may gradually lose its appeal in an uncertain policy environment. If the Labor government wants to truly reconcile the interests of both parties, it must start with institutional reform, rather than relying solely on the “suboptimal solution” of regulating the number of international students to deal with social contradictions.

Voice of the Witness

I interviewed Jason (pseudonym), a Chinese international student studying at La Trobe University in Melbourne. His situation is quite representative. He is an international student, And he owns a small house in Box Hill.

Jason, as a unique individual who is both an international student and a landlord, does not agree with the claim that international students are driving up housing prices. He believes that

rising housing prices are part of a normal market trend and have no direct connection to international students.

Additionally, he states that

whether the government raises visa fees or reduces the number of student visas, such policies would not have a substantial impact on him personally.

What should we really focus on?

BUILDER BUSTED… TWICE?

A Perth family signs with one builder — it collapses.

Signs with a second — also collapses.This isn’t misfortune.

It’s what happens when govts wreck the economy, jack rates, hike costs & drown builders in red tape.Australia’s housing crisis is… pic.twitter.com/KUy5eO3UbT

— Shallowchal (@shallowchal) May 1, 2025

People complain about the housing crisis in social media posts, Some people believe that the housing crisis is not caused by international students (foreign population), but by the government.

The efficiency of local governments in housing approval and land release has long been criticized. The approval stage for low- and medium-density residential development projects in many cities takes too long, resulting in the inability of new housing supply to keep up with the speed of population and urban development.

Public housing construction has been underinvested for many years. According to data from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), the proportion of social housing in the country has dropped from 6% in the mid-20th century to less than 3.5%. For low-income people and students, the buffer mechanism of the rental market is failing.

The structural injustice of the Australian rental market cannot be ignored either. Landlords have absolute dominance, and short, unstable leases and limited legal protection put many tenants in a passive position. Under this unbalanced supply and demand structure, any new population may be regarded as an “external force” to push up housing prices, rather than a reasonable urban carrying capacity.

Therefore, what is really worth paying attention to is not “who is coming”, but “are we ready?” Public policies should not be aimed at shifting responsibilities, but should focus on improving system resilience. Investing in basic housing facilities, simplifying the development process, and formulating long-term rental stability policies are the fundamental ways to alleviate housing pressure.

Be the first to comment