At the beginning of 2024, Lily, a newly arrived Chinese student pursuing her master’s degree in Australia, found herself caught in a drawn-out housing battle that lasted for weeks—before she even had the chance to enjoy the excitement of starting a new life.

Since she failed to apply for a dormitory on campus, Lily had to look for a social apartment. In February, the peak enrollment period, housing supply was tight, and many landlords took the opportunity to raise prices and were very strict in their tenant screening, making it difficult to find a room.

“I worked hard sending out applications and inspected tons of places. The agents said having local rental history and a job guarantee would boost my chances, but I had just arrived and had none of that, so the application was basically ignored.”

Two weeks later, she ended up renting a tiny 13-square-meter room for a steep $759 a week.

“When I saw the news blaming international students for the rental crisis, I was really angry. International students are already a vulnerable group.”

Our rental situation is more difficult than that of locals or most immigrants. We also bear the pressure of high rents. Why should we be the target of blame? ”

Australia’s rental crisis worsens, but international students become scapegoats

In August 2024, the Australian government announced that it would cut the number of international student visas from 2025 and limit enrollment to 270,000 in order to ensure a more equitable and sustainable education system and strengthen the integrity and quality of international education.

At the same time, Australia is experiencing a severe housing and rental crisis in recent years, with the national rental vacancy rate remaining at just 1.0% according to SQM Research.

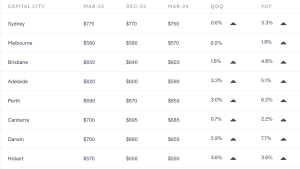

The Domina Rental Report shows rents for houses and units are at record highs in all capital cities, with growth slowing but still continuing to rise.

In April 2025, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton publicly stated that reducing the number of international students could solve the housing affordability problem for young Australians.

Data proves: International students have no direct relationship with the rental crisis

Despite the growing public backlash, there’s little data to support the claim that international students are making the rental crisis worse. On the contrary, international education contributes $51 billion to the Australian economy each year.

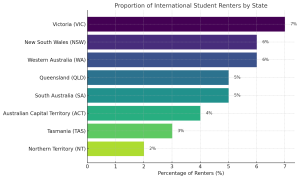

According to a report released by the Property Council of Australia, International students only account for about 6% of the entire rental market in Australia. This includes purpose-built student accommodation. These properties do not directly compete with the rental market.

This suggests that, even though there has been an increase in overall numbers, the impact of international students on the overall rental market has been greatly exaggerated and that they cannot be blamed for the current widespread housing crisis.

Michael Mu, an associate professor at the University of South Australia, said the research team took into account the number of international students, rental vacancy rates, inflation and rental costs, and concluded that this was a supply problem. The correlation between international students and the rent surge was random and there was no actual pattern.

International students are the silent victims

“I have friends who’ve dealt with landlords suddenly raising the rent or making other unreasonable demands, but most of them stay quiet because they’re afraid it might affect their visa or studies. They’re also not familiar with the rules, so they don’t feel confident making a complaint.”

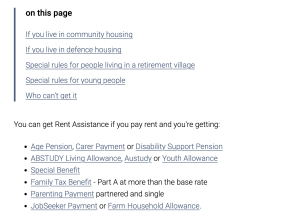

In Australia’s highly market-oriented housing system, international students, as outsiders, are on the margins of the rental market. In addition to facing high rents, the entire system lacks the most basic acceptance and protection for international students. Most housing subsidy programs are not open to international students, and there is invisible institutional discrimination.

This graphic from the Services Australia website shows that tenants can only apply for rental assistance if they are receiving certain government subsidies.

“I have also learned about the NARS program, but there are very few places and it is too difficult to apply.”

NRAS (National Rental Affordability Scheme) was launched by the Australian government in 2008 to help increase the supply of affordable rental housing. Approved participants can rent housing at a price at least 20% below the market rent. However, with the end of the ten-year incentive period, all homes in Queensland and Victoria will be withdrawn by June 2025.

This series of policy systems have exacerbated the vulnerable position of international students in the rental market, leaving them with almost no room to speak out, making it more difficult for them to seek legal or government assistance when they encounter problems, and they gradually become silent victims.

Focus on the real problem

Housing is a key component of social equity and economic stability. The main reason for the housing crisis is insufficient supply. According to the “2025 Land Status Report” released by the Urban Development Institute of Australia (UDIA), the housing supply gap in capital cities is worrying. By 2029, the total number of housing units nationwide will be about 393,000.

Even if the number of international students were completely reduced, it would not be enough to ease the tight housing market. The real problem is not “who rents the houses” but “not enough houses are built.”

In addition, more deep structural problems have been exposed that affect the ability to rent:

- Population growth has increased housing demand

- The cost of living crisis has squeezed the space for daily expenses.

- Slow land development policies and increased housing construction time

- Insufficient supervision of rental platforms and subsequent guarantees cannot be guaranteed

- The short-term rental market has higher returns, thereby reducing the available rental volume

- The investment housing market is dominant, squeezing the space for ordinary tenants.

Society shifts the blame to international students, which is actually to cover up the policy and system problems that should be questioned. The real solution should be to urge the government to reform the housing policy system, rather than creating public opinion that creates identity confrontation.

Interview with Lily (pseudonym), an international student at the University of Sydney:

Be the first to comment