When people talk about Australia’s housing crisis, the conversation often focuses on house prices, interest rates, and financial burdens. However, another dimension of this crisis is often overlooked: it is eroding people’s mental health. Vincent Bai, a Sydney real estate practitioner, confirmed this with his first-hand observations:

“Young people are under great pressure to buy a house for the first time. Many couples keep arguing during the house viewing process, and anxiety and tension can be seen everywhere.”

This is not an isolated phenomenon. According to the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), housing instability is closely related to symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and mental breakdown, especially among young people.

The housing crisis is not simply an economic problem, but also a growing public health crisis that demands immediate attention.

From Psychological Stress to Mental Illness: The Starting Point of a Vicious Cycle

Housing unaffordability not only affects residential stability, but can also trigger or aggravate mental illness. A study published in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology pointed out that people who have experienced long-term housing affordability stress (HAS) have significantly lower mental health scores.

Once psychological problems arise, they will, in turn, weaken the individual’s social skills, job-seeking willingness, and work performance, further exacerbating the plight of economic difficulties and unstable housing. This closed loop of housing difficulties, mental illness, impaired functioning, and further hardship makes it increasingly difficult for individuals to break the cycle on their own.

In support with this view, a report jointly released by Mind Australia and AHURI in 2020 found that people with severe mental distress are 89% more likely to face financial difficulties in the next year and 96% in two years, and those who have been diagnosed with mental health problems have a 39% increased risk of being forced to move within a year. The relationship between housing problems and mental health is not linear, but rather a systemic dilemma that is intertwined and exacerbated in a cycle.

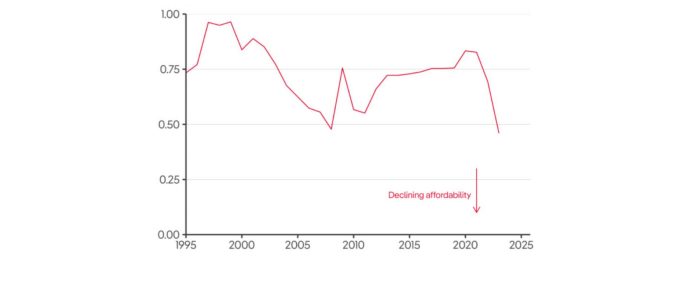

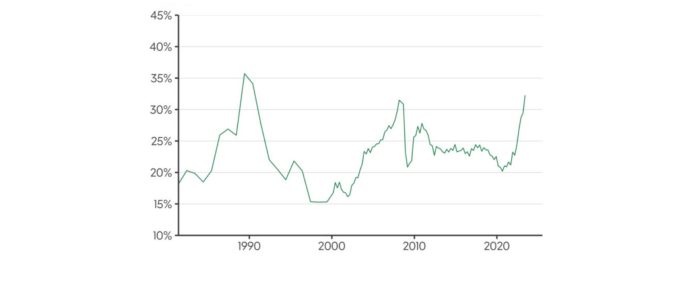

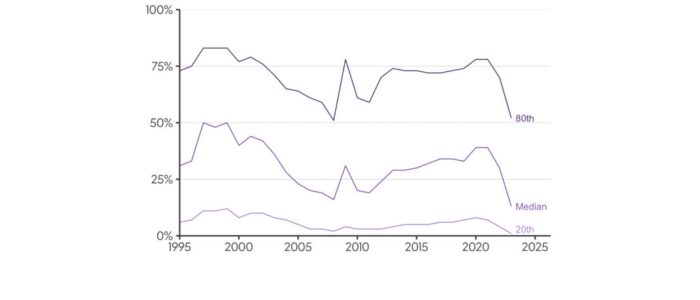

Graphs Illustrating Australia’s Housing Crisis/Source: PropTrack

What Measures Were Taken?

The federal government has proposed the National Housing Accord, promising to build 1.2 million new homes by 2030 and supporting the promotion of the “Build-to-Rent” model. However, the policy has been slow to implement. The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) projects that, at the current rate of construction, Australia will fall short of its housing target by approximately 262,000 homes.

BREAKING: Australia’s Build-to-Rent

Were you aware Albo’s Labor govt is providing foreign institutional investors with concessional tax rates to build thousands of new homes for RENTAL ONLY with a concessional tax rate of just 15%

Labor is intentionally killing home ownership! pic.twitter.com/pc1SL0SNUK

— Aus Integrity (@QBCCIntegrity) May 19, 2025

Policy pilots centred on the Housing-First approach have shown significant intervention effects. Individuals who have access to stable housing have significantly better use of mental health services and recovery outcomes than those who have not received such interventions, proving that housing itself is an effective mental health strategy.

Frontline Voice: Housing Anxiety is Real and Heavy

The interview with Vincent Bai further confirmed the reality of policy lag. Bai noted that with interest rates now at 6–7%, many home buyers struggle to afford monthly repayments, even with stable jobs. He added that for those looking to purchase a home, making a down payment is often impossible without financial support from their families, creating immense pressure. Bai also shared that he frequently takes clients to view lower-end properties, which usually leads to tension or disputes due to poor conditions or tight budgets.

He pointed out that not only are young people feeling weak, but the high-end market is also under pressure. Many potential sellers are holding off due to high transaction costs, market uncertainty, or difficulty upgrading in a tight market, which further compresses the market supply. This double squeeze on both the “selling” and “buying” ends has exacerbated market tensions.

Social Support & Mental Health

Although there are joint housing-mental health programs for vulnerable groups such as HASI, their scale is limited, and most regions still lack an integrated two-way support framework. Mental health support systems are mostly independent of housing policies, and housing policies rarely consider the mental well-being of residents. Studies have shown that if social support—such as counselling, peer networks, and local community resources—can be embedded within housing policy, the risk of housing instability decreases significantly, and the recovery timeline for mental illness is often shorter.

Why Has the Mental Health Issue Been Neglected for So Long?

From a cultural perspective, Australian society often regards housing as a symbol of personal struggle, and the mainstream narrative emphasizes that “as long as you work hard, you can afford a house.” Therefore, housing inequality is often attributed to individual “economic failure” or “laziness” rather than deeper structural problems. This narrative not only conceals the institutional barriers behind the real estate market, but also weakens the public’s understanding of “housing as a health issue” and even stigmatizes psychological difficulties.

A survey reveals that, although 81% of Australians agree that “people may fall into poverty for non-personal reasons”, public attitudes often shift toward moral judgment when it comes to specific assistance measures. This attribution bias is particularly evident in housing issues, making it challenging to implement institutional responses to housing difficulties.

Structural understanding should be the starting point for exploring public issues. In addressing the housing crisis, we must eliminate the binary opposition between “house speculators” and “losers” and refocus on the gaps in institutional support and the lack of public services.

Redefining the Housing Crisis

Housing is not only about shelter but also about dignity, stability, and belonging. When what you can’t afford is not just the “dream home” but a basic residence, one must treat it as a public health issue. Vincent Bai notes that many of his clients are not investors, but everyday people buying homes to live in. Yet even among these buyers, joy is often absent.

They’re anxious, conflicted, and under immense pressure. For most of them, buying a house doesn’t feel like achieving a milestone. It feels like surviving a crisis.

Now, it is time to treat the housing crisis as a mental health emergency and ensure this reality is reflected in Australia’s policies, community strategies, and public conversations.

Be the first to comment