On May 21, a Chinese couple was violently attacked by a group of children in the Eastgardens area of Sydney. Seven suspects have been charged and are still

under investigation. They are aged between 12 and 16 and have been granted conditional bail to appear in the Children’s Court in June. This incident caused an uproar on the Chinese social media Xiaohongshu (Rednote).

Currently, the case is still under further investigation. The victim couple suffered varying degrees of physical and psychological trauma. There are more than hundreds of related posts on Rednote, with many users calling for the organization of voluntary patrols and legal aid, while recording the street violence they have experienced or witnessed in an attempt to arouse more attention.

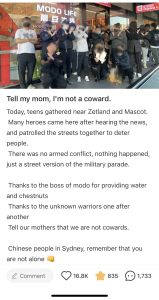

The anger of the Chinese community was not only superficial but also manifested in action. They have completely entered a “wartime state”. People connected with each other to provide help and protection to each other. They took to the streets where young criminals often appeared. This was called the “street version of the military parade” by them.

On June 1, Rednote user @Augustus released a Chinese website called Escort Sydney. On this website, users can “seek help with one click” and mark dangerous places. Shop owners can mark their shops as “safe houses” for people to take shelter.

The Attack still not Considered Racist![]()

Safety is one of the important reasons why many international students choose to come to Australia, but before entering Australia, they are warned to be careful of “teenagers”.

Meanwhile, several verbal and physical attacks have also occurred in Maruba, Zetland, Waterloo, Randwick, Mascot, Redfern and Heymarket.

Erin Chew, co-founder of the Asian Australian Alliance, said that, “A lot of us who are Chinese or Asians know that because of racial stereotypes … you are perceived as being weak, meek and … somebody that doesn’t fight back.”

NSW Police had declined to confirm if the Eastgardens attack was racially targeting Chinese people, as their investigation was ongoing.

Warning Effect of the Law Ineffective in Dealing with Youth Crime

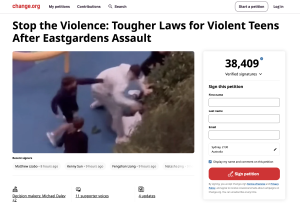

As of June 1, more than 38,000 people have signed a petition calling for stricter youth criminal justice laws.

In this petition, the first demand is “Lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility to 10 for serious violent crimes.” However, in New South Wales, the minimum criminal age (M

ACR) is 10 years old.

In fact, this is a very controversial legislation because the minimum criminal age is too low. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child recommends that MACR be no less than 12 years old and encourages countries to raise it to 14 years old or higher.

The discussion about youth crime seems to be caught in a paradox. On the one hand, Australia is already one of the countries with the lowest age of criminal responsibility in the world and has been criticized for this. Statistically, there is no trend of an increase in the youth crime rate.

On the other hand, youth crime is one of the most significant problems in this country. The Liberal National Party even made “adult crime, adult time” – a slogan originated in the United States and a legal logic – one of its campaign promises.

Earlier, New South Wales announced that it would review the principle of doli incapax – Latin for “incapable of evil”, an important legal presumption regarding youth crime.

In New South Wales, the MACR is 10 years old, and doli incapax applies until the age of 14. In practice, the principle can be overturned if the police can prove that the offending child knew that the act was “seriously wrong”.

In the NSW Children’s Court, the proportion of convictions or innocence for children aged 10 to 13 fell from 76% in 2015-16 to 16% in 2022-23.

In Western Australia and Queensland, where “doli incapax” is written into legislation – the proportion of convictions has not changed much. Statutes define the specific scope of application of this legal presumption, making it easier to overturn.

No one wants to put children in jail, but it seems that children are not afraid. The law seems to have lost its warning significance to children.

What is the problem?

After the Eastgardens incident, many Chinese in Australia shared their own stories.

Jiajia, who would like his name changed, mentioned that on a New Year’s Eve many years ago, he was verbally attacked by four young people while waiting for a train to go home at a train station in the southern suburbs of Sydney. He exchanged half a bottle of whiskey left over from the dinner for their politeness.

In a later conversation, he learned that these young people came from a country in Eastern Europe and came to Australia with their parents at a very young age or were born in Australia.

“If they can communicate with, you can try to talk with them. If you leave without saying a w

ord, you will be attacked.” This is the experience given by Jiajia.

In April this year, Maodong, a Chinese stand-up comedian, came to Australia for a tour. He also has an entertainment podcast called “City Survival Guide”. He inviteslocals to share their experiences of living in the local area.

During the recording of “Sydney Survival Guide”, the topic of “teenagers” occupied most of the time, and many people shared their experiences. Near the end, a man sitting in the last row spoke, “I used to be one of those children you talked about.” He shared his experience: came to Australia at the age of ten, did not speak the language, and gained a sense of belonging through collective evil in a small group.

During the recording of “Sydney Survival Guide”, the topic of “teenagers” occupied most of the time, and many people shared their experiences. Near the end, a man sitting in the last row spoke, “I used to be one of those children you talked about.” He shared his experience: came to Australia at the age of ten, did not speak the language, and gained a sense of belonging through collective evil in a small group.

When asked about his motivation, he mentioned loneliness. “Endless loneliness. When I realized that evil against society could not really alleviate loneliness, I got out.”

Be the first to comment