Content Note: This article contains references to mental illness, therapy access, and indirect references to eating disorders.

The Medicare therapy session cap in Australia quietly entrenches one of the country’s most overlooked health crises. Mental health issues affect millions of Australians, yet access to psychological care remains rationed by a system designed around quotas, not need.

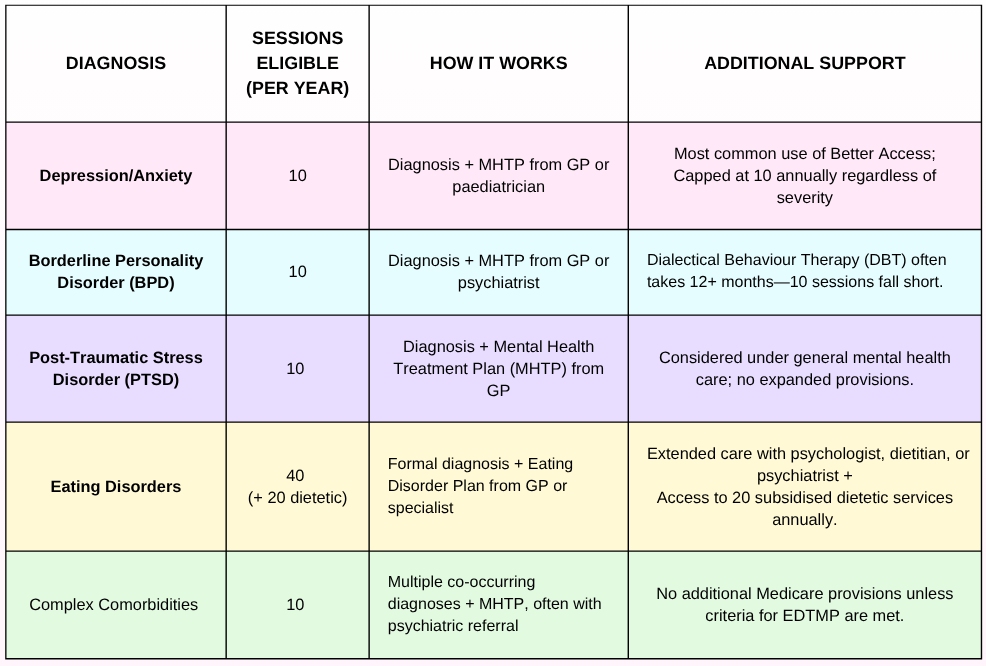

Under the Better Access initiative, most Australians are eligible for just ten Medicare-subsidised individual therapy sessions per year— whether they’re managing mild anxiety or the long tail of complex trauma (Services Australia, 2024). Those with eating disorders may qualify for up to 40 annually, but others are cut off mid-recovery without recourse (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2024).

This one-size-fits-all cap ignores clinical realties, and mental health professionals warn it often withdraws support just as therapy begins to work.

With over 40 per cent of Australians aged 16–85 experiencing a mental disorder at some point in their lives (ABS, 2023), needs-based care isnt just preferable, it’s urgent.

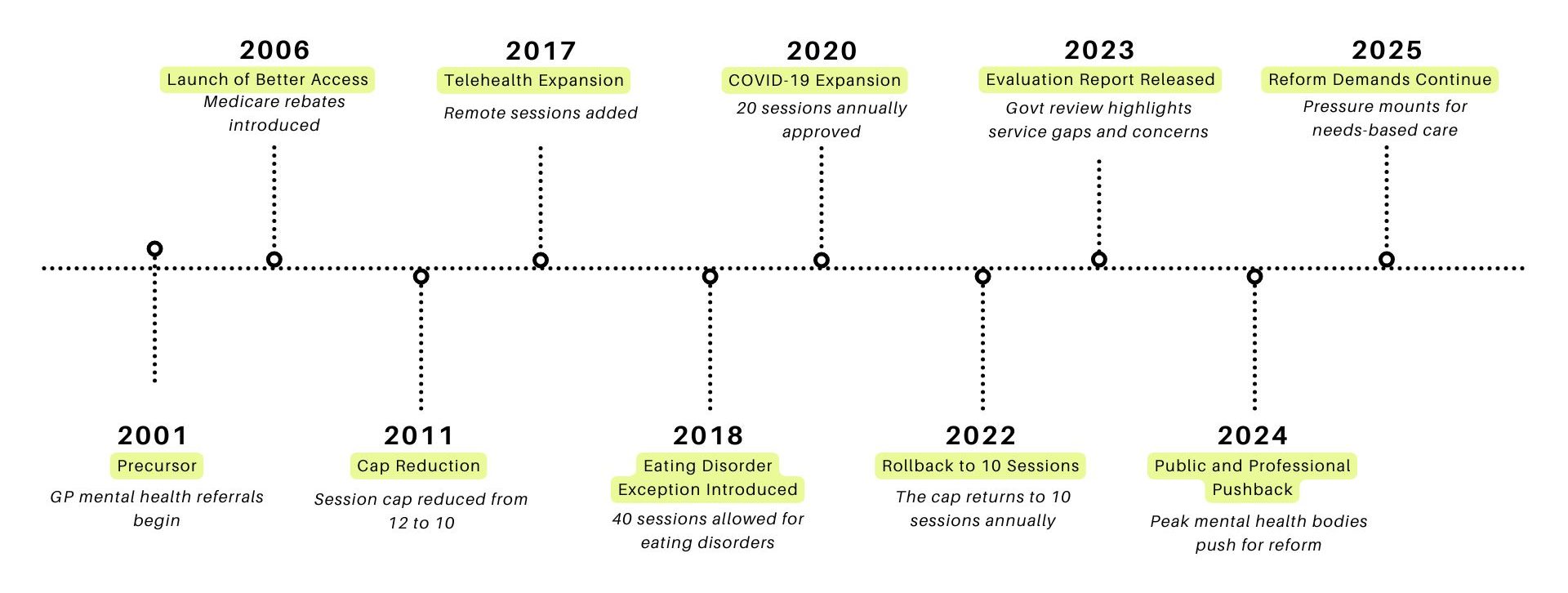

The History of Better Access

Launched in 2006, The Better Access program aimed to improve mental health supoport through Medicare rebates for psychology, psychiatry, and GP mental health plans. It now represents the single largest government investment in mental health services.

But the flat-rate 10-session limit has failed to revolve with growing demand for more nuanced understandings of care.

During the COVID- 19 pandemic, the cap was temporarily doubled to 20 sessions. Evaluations found this expansion improved outcomes for patients with complex or high-risk conditions. Yet despite this success, the government rolled the measure back in 2022, citing budget concerns over clinical need.

The Two-Tier System the Cap Created

Mental illness is now Australia’s leading chronic health condition, with over 4 million Australians affected annually.

Yet, the capped structure of Better Access creates a stark inequality: those who fit neatly into defined clinical categories receive extended care, others dont— regardless of severity.

The result is a two-tier system. Patients whos condition qualify for extended support receive adequate care, the rest are left to fund additional sessions themselves or abandon treatment all-together. With private therapy costs sitting at $311 per session in 2024–25, many Australians simply cannot afford continued care.

“When I found out that people with eating disorders can access up to 40 sessions… I felt angry — not at them, but at the inconsistency of support. PTSD and bipolar don’t disappear after 10 sessions either.”

Hitting the 10-session cap can feel like stepping off a cliff.

“Instead of feeling like I had time to heal, I felt like I had to make every moment count, which is a lot more pressure when you’re really vulnerable.”

For many, therapy is not a short-term fix. Clinical evidence shows that meaningful clinical improvement most often occurs between sessions 6 and 12. But ending therapy right when this takes place doesn’t just delay recovery—it risks deterring people from ever returning

To put it plainly: Patients aren’t discharged because they’re well—they’re discharged because their sessions are up.

The Human Cost of a Number

Behind the data lies a more painful reality.

The Medicare therapy session cap creates real-world disruption for those in crisis.

To understand what this feels like on the ground, this article includes insights from a university student who received therapy under Better Access in 2024:

Due to the sensitive nature of the discussion, medical personnel identity is removed from the interview to protect their privacy—but their account reveals the emotional arithmetic many Australians face when care is capped by policy, not progress.

Australians navigating grief, suicidal ideation, or trauma face a crucial choice: pay out of pocket or walk away from care. Some patients have turned to Buy Now, Pay Later services to continue seeing their psychologist. Others are forced to stop due to policy constraints.

“I just didn’t have the resources to keep going”

But beyond the financial strain, the cap enforces a more insidious psychological toll: the need to be “sick enough”.

Mental illness can be very competitive, where only the “sickest” deserve care. The cap reinforces this mindset, pressuring people to compare and measure their experiences agaisnst rigid criteria. Unless visibly or diagnosably unwell, many feel like they don’t deserve help. This only deters early intervention, worsens clinical outcomes, and replaces support with shame.

“”It made me question whether I was truly deserving of care… Knowing there was a cap made me feel like I was being told, ‘you’ve had enough now — you don’t deserve more.’”

Their experience echoes what mental health professionals have long warned: healing isn’t linear, and it isn’t finished in 10 sessions.

Let Clinicians, Not Calendars, Decide

If physical health isn’t rationed by arbitrary quotas, why is mental health?

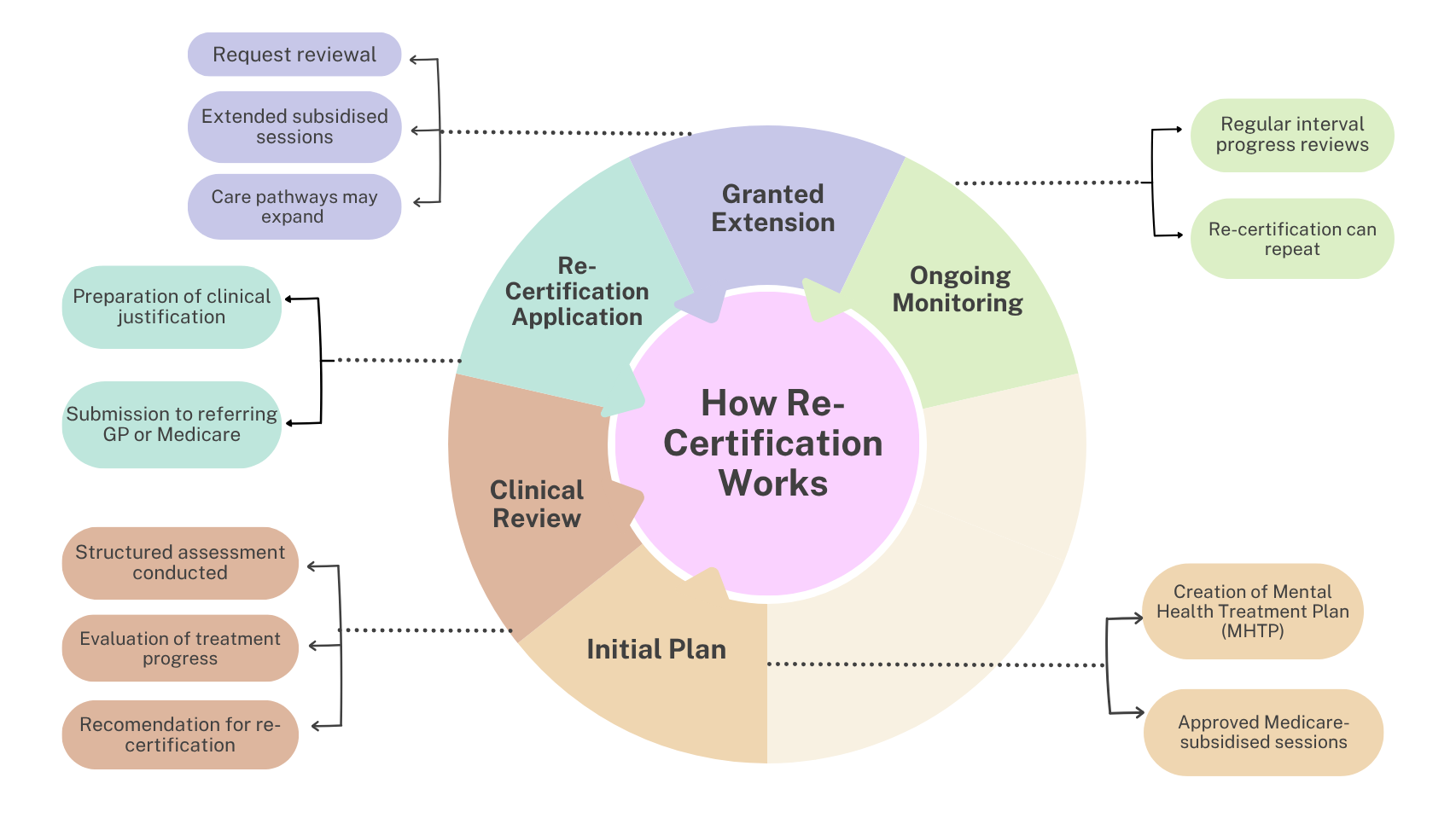

That’s the central question posed by a growing coalition of clinicians and consumer advocates. And a re-certification model could end arbitrary Limits; we’ve seen it work before.

This model would let qualified professionals, not policy makers, to extend treatment beyond the tenth session, based on clinical judgment.

“It would’ve changed everything. I would still be in therapy now.”

Working models like this already exist. The UK’s NHS stepped-care model offers personalised therapy pathways that adapt to a patient’s needs over time.

This approach reflects a basic principle: care should be driven by clinical judgment, not calendar limits. And a re-certification could just be the solution to the Australias Medicare therapy session cap.

Time’s Up on Timed Care

Better Access helped destigmatise mental health and expand access—but it’s no longer fit for purpose. Ten subsidised sessions per year, for all conditions and complexities, is a failure of policy imagination and clinical logic.

The evidence is clear. The models exist. The demand is overwhelming. Recovery doesn’t run on a schedule—The care Australians need shouldn’t either.

This isn’t a matter of budgetary restraint.

It’s a matter of political will.

If Australia is serious about mental health, it must stop treating it like a cost centre. The system needs more than patchwork fixes. It needs structural reform.

Mental illness is real, and support is available. If you or someone you know needs help, contact:

- Lifeline – 13 11 14 or lifeline.org.au

- Beyond Blue – 1300 22 4636 or beyondblue.org.au

- 13YARN (First Nations Support) – 13 92 76 or 13yarn.org.au

- Headspace – 1800 650 890 or headspace.org.au

Be the first to comment