Amy Chen, a university student, 21 years old, saw a strange mole growing on her shoulder and thought it was nothing—just a normal effect of going to the beach all summer. Like many of her friends, she didn’t think sunscreen was necessary unless it was hot enough outside. After one year, she was diagnosed with early-stage skin cancer.

Stories like Amy’s are common in Australia. Cancer Council Australia indicates that about two thirds of Australians will get skin cancer at some point in their lifetimes. This makes the country become one of the highest rates in skin cancer around the world. In Australia, there are about 19,000 individuals with invasive melanoma and another 28,000 cases of melanoma in situ are reported each year.

Long-term exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the main reason. UV radiation can damage skin cells permanently. This damage builds up gradually, which means that even short periods of time spent in sunlight without protection may cause a long-term effect.

Alex Fan, a 25-year-old student at the University of Sydney, says he didn’t use sunscreen very often when he came to Australia. “I didn’t think about it too much,” he adds. “Everyone loved embrace sunshine here, so it was normal, even though I knew my skin was burning faster than usual, I didn’t pay much attention to it.”

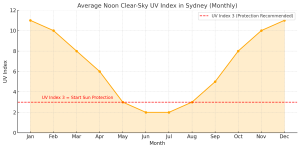

It’s not just Alex. More and more young people don’t use sunscreen and are unaware of how harmful UV rays can be. Many people consider sun protection as something to do in the summer, but an article from Bureau of Meteorology highlights that UV levels are still high and unhealthy for skin in autumn and spring. “There’s no UV ‘off season’ for most of Australia,” it says, which means that people in places like Sydney need to protect themselves all the time.

UV energy is undetected and cannot be seen, unlike heat or light. The article says, “Since you can’t see or feel UV, you won’t know the damage has been done until it’s too late.” The effects build over time, and for many people, the first sign is getting older faster than they should, especially in people under 50.

Skin that has been exposed to the sun over and over again without protection, it often gets wrinkles and sunspots. A UV index chart from the article shows how average daily radiation levels in Sydney often exceed the recommended limit for sun protection, even during spring and late autumn.

(Figure 1: Average daily UV Index in Sydney. Source: Chart created by author based on Bureau of Meteorology data.)

“It wasn’t even hot—just a cloudy 22 degrees Celsius day in spring—but I still got sunburnt,” Alex says. “That’s when I realized how misleading it is. You can’t just rely on how hot it feels.”

Despite decades of public campaigns such as “Slip, Slop, Slap,” research by the Cancer Council shows that sunscreen use among young adults remains inconsistent. Social media may be part of the problem. On platforms like Instagram and TikTok, bronzed skin is often framed as a sample, enhancing the idea that tanning embraces health and confidence. Alex explains, “I used to think that a little sun wouldn’t hurt. It gave me the impression that I was just taking in the scenery like everyone else. I was unaware of how rapidly the harm could happen.”

(Figure 2: Video: Slip! Slop! Slap! Source: Cancer Council Australia Platform: YouTube)

His problems got me thinking about the changes of my own perspectives on UV protection. Furthermore, I have witnessed that Australia and Asia have a bit different cultural backgrounds about protection from sun lights.

Many East Asian countries, where most people have naturally yellow-toned skin, prefer more pale looks. This belief also be deep-rooted and encouraged by social media and public, leading to an eastern beauty standard. They prefer lighter skin tone, youth, slim body, and a “white” appearance. In Australia, on the other hand, tanning is generally considered as a sign of good health and an enjoyable way of life. Sun exposure is not only accepted but also very appreciated. In Australia, bronzed skin is seen as evidence of social acknowledgement or physical ability. While many Australians consider tanning to be beneficial and an approach to boost confidence, East Asian societies are more likely to consider tanning as a sign of damage.

I grew up in China, so I knew about this weird condition. As for me, though I’m 24 now, I started using sunscreen regularly at around 15, just because I didn’t want to get any darker, not because I was worried about any health risks. But after learning more about the harm of high UV rates, I realized that such healthy protection habits were more important than just had a lighter look. These habits were useful for skin health, protection, and even my future lifetime. It is kind of funny, but what I considered as a beauty routine gradually influenced my decision of getting a healthier body.

Still, many young people make their decisions just on temperature or sunlight levels instead of knowing the real UV rates from mobile applications or daily forecasts. One of the challenges is to change their perspective. Although the risks are obvious, changing someone’s behaviour is more difficult to achieve. Online media platforms, universities, social organizations should encourage people to embrace sun protection. Events combining visual impact with safety—such as displaying fashionable people wearing sun-protection jackets, glasses—may be more successful than just advocating its advantages.

At the University of Sydney, Alex now keeps a bottle of sunscreen in his backpack and checks the UV index each morning. He’s also talked to his friends about rethinking their sun habits. “Once I understood the risks, I realized that I can’t do what I chose to do in the past,” he says. “But I can make better choices from now on.”

Be the first to comment