On October 1, 2024, the application window for the Working Holiday Visa (WHV, category 462) for applicants from the Chinese mainland in Australia reopened again.

This marks the Australian government’s reopening of the WHV application after 154 days since the suspension was announced on April 30, 2024.

Embassy of Australia in China: Work and Holiday (subclass 462)

When the “Notification of Registration Selection” email popped up, Ms. Nyx (a pseudonym) had difficulty controlling her excitement.

She became one of the 5,000 lucky Chinese to successfully apply for an Australian working holiday visa in 2024.

A Record-breaking Rush for Visa Applications

According to the Australian Department of Home Affairs, the Working Holiday Maker (WHM) program for the 2023-24 academic year received a total of 253,606 visa applications from various countries around the world.

Among them, the number of applications from China exceeded 40,000. However, there are only 5,000 visa quotas for China, which means the winning rate is only about 12%.

These data highlight the changes in the geographical distribution of WHV holders.

Among them, the United Kingdom, France, the Republic of Ireland, Japan and South Korea, as well as Indonesia, the United States, Argentina, Thailand and Vietnam are the five countries with the most WHV subclass 417 and 462 respectively.

With an increasing number of Asian applicants flocking in nowadays, the WHV landscape, which was once dominated by backpackers from Europe and America, is gradually being restructured.

This reflects broader regional mobility and people’s interest in working holiday opportunities in Australia.

“Work & Vacation” –the Interweaving of ideals and reality

When the Australian Immigration Department launched the WHV in 2005, the front page of the policy document was printed with a striking slogan “Give your youth an adventure”.

When nearly two decades have passed, the new influx of backpackers is reshaping the background of this policy with more complex motives.

The cross-border research conducted by Hayato Nagai, a scholar of immigration studies at the University of Tokyo (2018), reveals the four core driving forces of Asian applicants, namely language improvement, cross-cultural experience, economic gains and life restart.

These motives seem scattered, but in fact, they all point to the young generation’s desire for the ability to survive in globalization.

On social media, showing off a weekly salary of 2,000 Australian dollars has become a new traffic code.

Source: Xiaohongshu (RED)- a Chinese lifestyle and social commerce platform

On the surface, it is a myth of a working holiday’s success. However, in reality, it is a false traffic trap meticulously fabricated by unscrupulous agencies.

These contents are precisely pushed through algorithms, taking advantage of the overseas gold rush dreams of young people, and ultimately leading to a fraud chain of high agency fees.

In terms of policy design, WHV is becoming an invisible pillar for specific industries.

According to the visa terms, the holder can work for the same employer for up to six months. If they engage in agriculture, fishery or construction in the designated remote area for 88 days, the second-year visa will be unlocked.

Beneath the Halo: The Survival Challenges of Visa Holders

Countless applicants carry the double illusion woven by social media before setting out. While the left hand touches the warm waters of the Great Barrier Reef, the right hand takes the salary envelope of 2,000 Australian dollars per week.

In reality, most WHV holders work on the farm for long hours while worrying about expensive accommodation and uncertain job opportunities tomorrow.

Nyx, who is 30 years old, showed me various job-hunting software installed in the mobile phone, such as Seek, Indeed and various official websites. “I have been trying to submit my resume online, but there has been no reply. Later, I kept following the fb group and found my first farm job,” she said.

She spends several hours every day browsing job search platforms, and information asymmetry has become the biggest obstacle.

Unstable work is a common pain point. WHV holders are mainly engaged in temporary positions such as service industry, farm workers and house keepers.

“Both of the two farm jobs I have been doing so far are casual, with a working day of up to 10 hours,” Ms. Nyx said helplessly, “There is no pay raise for overtime or public holidays, but it seems everyone is used to it.”

What is concealed is the loophole in rights protection. According to regulations, WHV holders should enjoy the same labour protection benefits as local employees.

Trade union organizations have found that about 30 percent of backpackers have experienced salary deductions due to visa validity restrictions and employers taking advantage of information gaps.

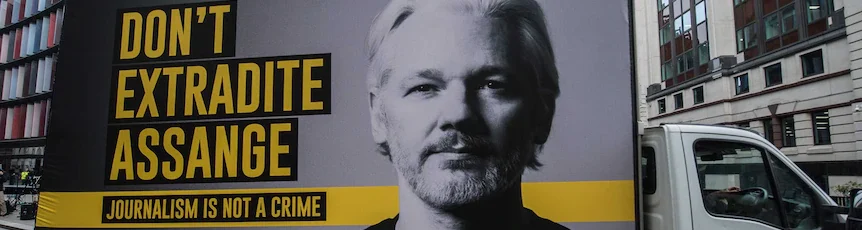

The Political Arena is Embroiled in a Tug-of-war over Visa Policies

The WHV policy has become a sensitive issue in the confrontation among political parties in Australia.

Since the end of 2023, the Albanese government has rolled out a series of immigration policy reforms, aiming to control the net scale of overseas immigration and reduce reliance on temporary labor.

Although these policies have not yet touched upon the WHV category, they have to some extent raised concerns among WHV applicants and owners.

The coalition party chose a different stance. The coalition party has joined forces with tourism groups to protect the WHV system, which is regarded as the lifeblood of the regional economy.

Between economic recovery and the tug-of-war of votes, visa policies are constantly being politicized.

Behind this political tug-of-war, the originally flexible and diverse WHV system is gradually moving towards uncertainty and tightening. This has brought unprecedented policy ambiguity and movement restrictions to visa holders.

The path ahead: Policy adjustments on a tightrope

In the face of a rapidly growing number of visa applications, the Australian Immigration Department has initiated mechanism reforms.

The new lottery system implemented in 2024 replaced the previous online scramble for “whoever is faster”, trying to establish a fairer distribution system.

But deeper policy adjustments are still brewing.

Should visas be tightened to ease the housing pressure, or should the door be opened to preserve the $3.1 billion backpacker economy?

Behind each choice lies a different vision of Australia’s future.

Reference List

Department of Home Affairs. (2024). Working Holiday Maker visa report – June 2024. Australian Government. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/working-holiday-report-June-24.pdf

永井隼人, ナガイハヤト, ベンケンドルフピエール, & カチンスキアーロン. (2018). Exploring the motivations of Asian working holiday makers travelling to Australia. 観光学, 18, 43-53. https://wakayama-u.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/2000539/files/AA12438820.18.43.pdf

Be the first to comment