(feature article)

It All Starts with a Box

On a Saturday afternoon with the sun high, John and his friends gathered in front of the blind box after school. John opened the package carefully and looked into the rows of dolls on the cabinet shelf with excitement and hesitation. He has drawn the same amount three times, but still want to try again. As soon as the hidden edition came out, the friends exclaimed in surprise. He took out his mobile phone to capture the moment and a smile appeared on his face. And in the next moment, his eyes fell on the next blind box.

In China, this kind of collectible toy, known as “blind box”, has sparked a cultural craze among young people. Each box contains a series of figurines. Before opening it, the buyer has no idea which one they will draw. It is precisely this uncertainty that catches people’s eyes – turning simple shopping into a game about luck and emotions. Brands like Pop Mart have precisely built a complete blind box economic system based on this concept, combining “randomness”, “scarcity” and “social sharing”.

More and more people like John are taking the opening of the blind box as a daily form of entertainment. For them, the random surprise is not only a shopping behavior, but also an emotional experience: a controllable adventure. It is precisely through this mechanism that Pop Mart combines randomness, scarcity and social sharing, turning consumption into an emotional cycle.

The rise of the blind box economy reflects how young people seek a moment of excitement in their fast-paced lives. But behind this trend, new thoughts have also emerged – when our emotions are commercialized and the surprises we feel are designed, are we pursuing dolls or that fleeting sense of anticipation?

Inside the Blind Box Craze

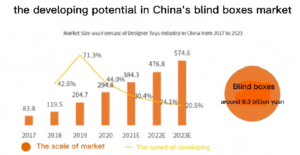

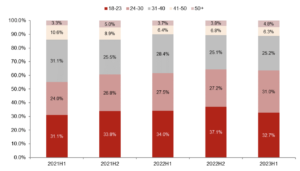

In just a few years, the blind box economy has evolved from being unknown to the public at the beginning to becoming a popular culture among young people now. As a representative brand in this market, Pop Mart has attracted a large number of consumers since it launched the “Molly” series in 2016 with its “random” and “limited edition” approach. According to Pop Mart’s 2023 financial report, the company’s yearly revenue is over 10 billion yuan, and its market share reaches about 9.3 billion yuan. Most of its clients are youngsters aged between 18 and 30 years. This proves that they are no longer mere toys, but a sort of new propaganda for consumption.

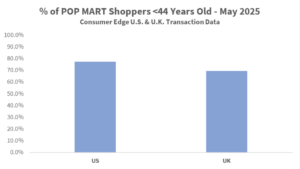

In the American market about 78% of consumers at Pop Mart are below 44 years of age, and youngsters are still the main consuming force. This data is close to that of the Chinese market where the age group 18 to 30 years predominates. It shows that the largest sphere of consuming are the young.

The investigation has also shown the psychological base upon which this mechanism rests. Xia et al. (2025) showed that the uncertainty of blind boxes can be the means of awakening the immediate satisfaction psychology of people, allowing consumers to enjoy a momentary emotional impulse in the act of opening the boxes. Pang and Zhou (2023) advanced the theory that these emotional fluctuations might lead to impulse buying and even mild addiction in some consumers. Tang et al. (2025) showed that the means of creating a sense of scarcity emphasizes this psychological force. When consumers think that opportunities are few and far between, they are more susceptible to repeated buying.

In addition there is to be found about blind boxes a keen social vein. A good many young people find personal prestige through the medium of shared pictures, exchanging, visiting and other means, thus making buying no longer a personal act, but one of a collective emotional character. As Wei and Yu (2025) pointed out, blind box consumption carries with it three forces. These forces are the error in cognition, the excitement or stimulus of emotion and the social chase that result in a changed philosophy of consumption, the new consuming process of young people.

All this has turned Pop Mart from a mere retail selling firm into a phenomenon of business with its center in emotions. It is able to catch the emotional force of young people in an ambiguous era and shows that the consuming culture of the period is changing from that of material consumption into that of emotional reaction.

People and Blind Boxes: From Consumer to Observer

For many young people, blind boxes are not just a shopping phenomenon, they are also a social experience.

Everly, a 21-year-old student from Sydney, said:

“When I opened the blind box, my heart raced, like winning the lottery.”

Everly bought her first Molly series blind box during exam week to reward herself. Her simple purchase turned into an everyday ritual of taking photos, posting on the Internet and discussing her rarities with friends.

“This is not just a doll. It’s also a collection that I can share with you, which gives me a feeling of recognition and achievement.”

Stella, 24, a Pop Mart shop assistant, observed similar behavior:

“Every day when I see the expectant look on the faces of customers coming into the shop, I know they are not just coming shopping but exciting a feeling of an emotional experience.”

She described how lighting, displays, and music create a sense of anticipation and ceremony. Customers often shake boxes, their faces showing both tension and excitement.

“In the shop, we create a sense of expectation and ceremony in the shop by lighting and display, as well as the way we display the limited editions. The neatly arranged boxes, soft lighting and cheerful music are attractive from an optical and auditory point of view.”

She also noticed that a lot of their clients shake their boxes before they buy them. The expression on their faces betrays no little flare of excitement, She said, “Some customers frowned as they drew the duplicate design and bought another box. From the expression on the faces of customers who drew the hidden box we know they screamed or got somebody to put it in.”

“The success of Pop Mart,” she added, “does not so much consist in the product in itself but that people have an impulse to try again.”

The interest of Everly and the observations of Stella show the real essence of the blind box economy, which is a game with small surprises in store and the shopping experience is one which is purely emotional and amusing.

Buying Feelings: The Emotional Side of Consumption

Pop Mart’s popularity is not accidental, but reflects some changes in the psychology of contemporary young people. Researchers believe that the essence of blind box consumption lies in the emotional satisfaction brought by “uncertainty”. In other words, what people buy is not just a doll, but the sense of anticipation that “maybe they will be luckier next time”.

Psychological research shows that the Random Reward System activates the brain’s reward system, causing people to secrete dopamine and thereby generating a brief sense of pleasure. Xia et al. (2025) found that when consumers are confronted with unknown outcomes, the feelings of tension and curiosity will superimpose, bringing immediate psychological satisfaction. Especially young people, they are more likely to seek this kind of short-lived happiness through frequent small purchases.

“Uncertainty itself is a kind of temptation. At the moment of unboxing, people experience not rationality, but emotion.”

— Frontiers in Psychology, Zhang & Zhang (2022)

From a social point of view, Pop Mart is a reflection of toy culture, but also a microcosm of the emotional state of young people. Pang and Zhou (2023) pointed out that in a very competitive and stressful social environment, young people hope to gain an emotional comfort through some “little joys”. The “probabilistic happiness” given by blind boxes just scratches this itch of emotion.

However, this circular consumption pattern also has potential dangers. Research by Tang et al. (2025) pointed out that when brands create anxiety by ways such as “limited quantity” and “scarcity” consumers can fall into emotional dependence – continuing to buy in order to maintain excitement and satisfaction. This will produce more impulsive consumption behavior over the long run.

The expressions of the customers Stella saw in the store were indeed a manifestation of this psychological mechanism: they were both anxious and in anticipation, and after disappointment would immediately light the candle of hope again. For the brand, this is a successful marketing strategy. But for consumers, it also means that their emotions are being precisely manipulated by business strategies.

The Ethics of Emotion: Are We Being Played by Design?

Behind the consumption boom of Pop Mart, a deeper question has begun to emerge: Is the brand taking advantage of human emotional mechanisms? In other words, when consumers are immersed in the excitement and anticipation of opening the box, is their happiness naturally generated or carefully designed?

The excitement people feel at the moment of opening blind boxes is actually related to the “dopamine cycle” in psychology. An unknown outcome brings about a random reward that stimulates the brain’s reward system, causing a brief sense of pleasure. This kind of pleasure often makes people repeat the same behavior over and over again.

“I spent $1,300 on ‘junk,’ but the feeling of anticipation kept me going.”

— The Guardian, 2025

According to a report by The Guardian (2025), a young consumer spent $1,300 on blind boxes in just three months. She knew very well that most dolls would eventually end up in the drawer, but still couldn’t resist the thrill of opening the box. This kind of “buyer guilt” and “addictive satisfaction” is becoming increasingly common.

Psychologists mentioned in the YouTube channel The Psychology of Shopping (2024) said that the use of random rewards and limited patterns by brands to satisfy consumers can confuse the line between reason and feelings. Here we can think of adolescents and young adults who unconsciously let their shopping behaviour be influenced by their feelings.

From an ethical point of view, there are also discussions about the phenomenon of “emotional capitalism”. When expectations, fears and loneliness can all be sold as goods, happiness is given a price. Sociologist Lee (2023) explains that contemporary capitalism commodifies “emotions”, which now become a good to be consumed. What people purchase is not happiness itself, but a temporary state of escape from reality. In other words, happiness has become a good of experience controlled by the market.

Finally, Pop Mart not only makes us reflect on our consumer behaviour but also reflects on where true happiness lies. In a world proliferated by emotions, how to strike the right balance between reasoning and desire may be the real question left to us by the blind box economy.

Conclusion

Pop Mart and the blind box economy transform consumption of young people from merely obtaining things to a complete reflection of their own emotions and their social experience. Through uncertainty, sense of scarcity and social interaction, the brands transfer the psychological mechanism into business logic and trigger thoughts related to the ethical and psychological aspects of these changes.

This consumer phenomenon reflects the trend of modern society: in a rapidly changing and highly competitive environment those things that people seek for are not merely material satisfaction but the moment enlightened by short emotional experiences. The surprises and expectations caused by the blind boxes make people strive for the balance between rationality and emotion and remind of the reflection whether happiness and satisfaction may be designed and commercialized.

Ultimately the blind box phenomenon reveals not only the consumption behaviour but also the deep concentration of contemporary young people concerning emotions, identity and belonging. It reminds one in our emotional world that what has more importance than buying more things is to understand and control one’s own desires.

Reference

Pang, Y., Song, Y., & Zhou, L. (2023). Exploring the psychological mechanisms of blind box consumption: The role of uncertainty and emotional stimulation. Journal of Consumer Behavior Studies, 15(2), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2023.02.004

Tang, J., Zhang, H., & Shao, L. (2025). Perceived scarcity and consumer impulsiveness: The moderating role of product type. BMC Psychology, 13(4), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-01234-5

Wei, Z., & Yu, B. (2025). Why do you engage in blind box consumption? The mediating effect of emotional gratification and the moderating role of social sharing. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-025-12345-6

Xia, Y., Chen, F., & Li, J. (2025). Unboxing desire: How uncertainty drives irrational consumption in the blind box economy. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-01185-9

Zhang, H., & Zhang, X. (2022). The effect of blind box uncertainty on consumers’ perceived value and repeat purchase intention: An SOR model approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 946527. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.946527

Colbert, L. (2025, April 10). My buyer’s guilt is insane: It’s $1,300 on trash. Yahoo! News. https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/articles/buyer-guilt-insane-1-300-140050905.html

Lee, H. (2023). Affective capitalism: For a critique of the political economy of affect. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-8174-8

The Psychology of Shopping. (2024, March 12). How your brain and emotions influence spending decisions [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yaMiYxsHuEs

The Guardian. (2025, August 18). ‘My buyer’s guilt is insane. It’s $1,300 on trash’: The adults addicted to blind box toys like Labubus. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/aug/18/labubu-blind-box-addiction-gambling

Zheshang Securities Research Institute. (2023, November 4). Pop Mart in-depth company report series (I): Mainland China chapter — Clearing the mist to see the sun, the changes and constants of Pop Mart. Zheshang Securities Research Institute. http://www.stocke.com.cn

Be the first to comment