After years of student complaints, UNSW is finally ditching its trimester model — but is the move too late for those who have already paid the price?

A long awaited change as UNSW ends trimester by 2028

UNSW’s trimester experiment is finally coming to an end—and for many students, it’s a relief. According to UNSW’s announcement, it will phase out the trimester model by 2028.

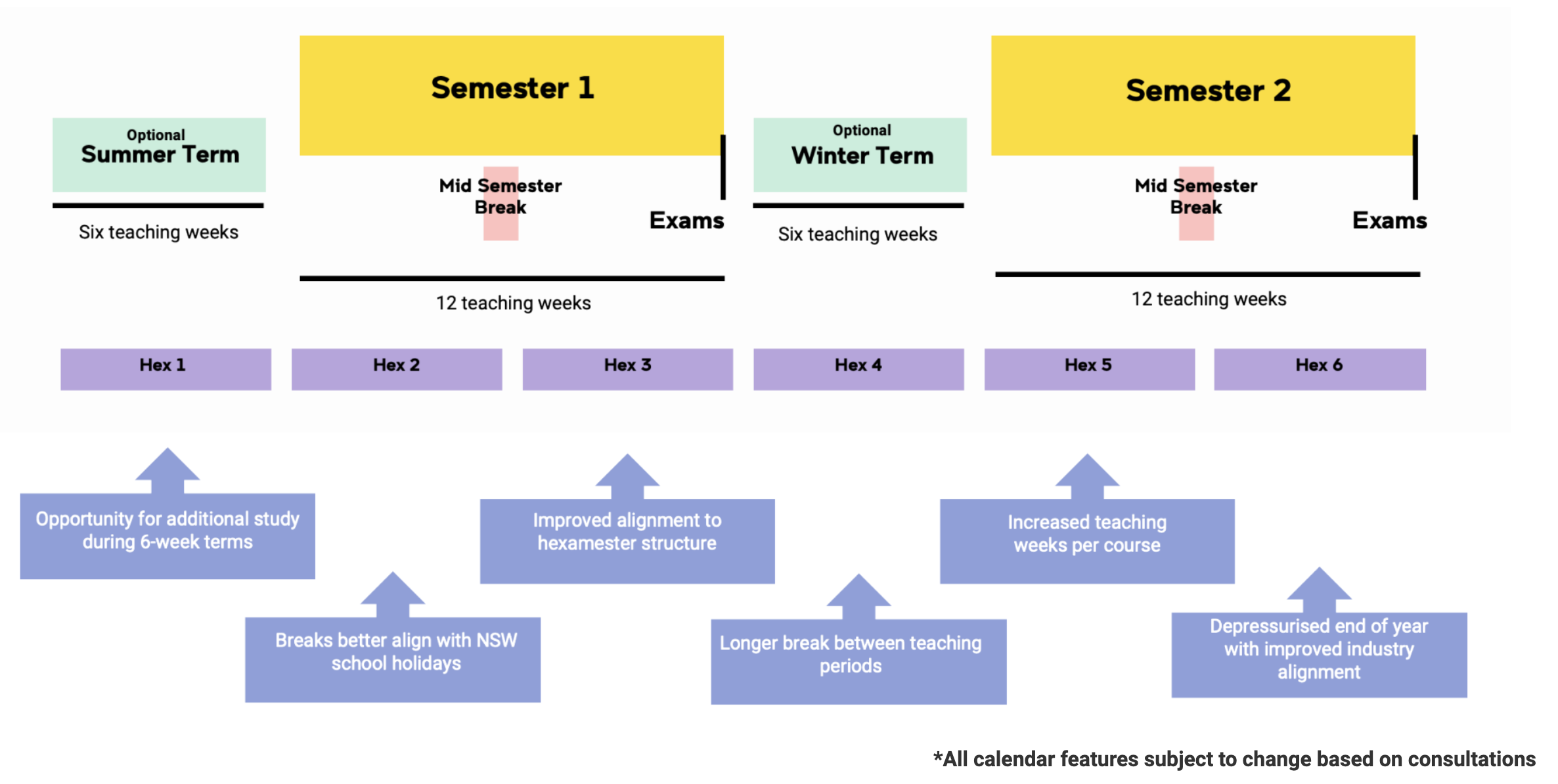

The new system will include two standard 12-week teaching semesters, mid-semester breaks consistent with school holidays, optional summer and winter intensive/remedial courses, and accelerated learning semesters. This will be in line with the current “six-semester” calendar of the University of New South Wales.

The decision came too late for many. They had already endured the system’s impact. Still, it shows that universities are starting to recognise students’ lived experiences. It marks a shift toward student-centered education.

UNSW3+ and global competitiveness

UNSW first introduced the trimester system (UNSW3+) in 2019, presenting it as a progressive reform. This system aimed at boosting flexibility and accelerating graduation timelines.

In its official communication, the university explained that the UNSW3+ model allows students to “tailor their study load across the year.” It also aims to make better use of campus resources throughout the year. University of California Press suggested that this change would enhance the international competitiveness of the university and student employability. On paper, the trimester system offered students a more agile and industry-oriented education pathway.

However, in practice, many students found the accelerated structure to be overwhelming. Each semester lasts only ten weeks. Students usually have to manage three courses. The heavy homework, reading, and deadlines leave little room for students to reflect or recover.

University of Abuja, FCT, Nigeria argues that the compressed timeline undermines the depth of learning, forcing students and lecturers to prioritize speed over content. Although UNSW positions this system as more flexible, many students report the opposite – the continuous semesters leave them with almost no time to rest or do internships. Ironically, this undermines a key goal of the reform.

A Model that Prioritised Speed Over Substance

For many UNSW students, the trimester system felt like a relentless sprint. Each term lasted only ten weeks. Students taking three courses often had to complete six major assessments in just over two months. “In fact, this mode did make me feel a little stressed because every term I only have ten weeks, but I need to take three courses,” a postgraduate student, Hannah Jiang, recalled. “So, in these ten weeks, I must finish six essays. A postgraduate media student recalled”.”

Transcript

1. How did you feel when you first heard UNSW was ending the trimester system?

Actually I feel a little nervous but then I found it starts from twenty twenty – eight, so that’s OK because it won’t impact me.

2.Will this change have an impact on your current studies?

Nothing will influence me because I will finish my studies in the third term of twenty twenty – five.

3.Do you feel the trimester system affected your academic stress or mental health?

In fact, this mode did make me feel a little stressed because every term I only have ten weeks, but I need to take three courses. So in these ten weeks, I must finish six essays. However, I like this stressful environment very much because it can help me keep studying.

4. Have you experienced burnout or insufficient breaks between terms due to the trimester model?

Until now, I have never experienced this. I even added a summer term to help me study more so that I can finish my studies more quickly.

5. What improvements or concerns do you foresee with the shift back to the two-semester model?

On the one hand, after changing to a two-semester system, the vacation time is divided into summer and winter, which is beneficial for students to find jobs. However, the course duration is extended, and it is possible that the time for students to complete their studies will also increase.

This interview is for a university assignment—would it be okay if I quote what you said? I can keep your name anonymous if you prefer.

The trimester system is designed to offer greater flexibility and multiple enrollments each year, but in reality, it sacrifices academic depth. It does not cultivate critical thinking and meaningful participation but forces students to rush through the content. Team YoungWonks argued that shorter school days can lead to increased focus during class. Students may find it easier to pay attention and engage in lessons without the mental fatigue associated with long school days.

By prioritizing speed and efficiency, this model regards education as a production line. But true learning requires time: time for asking questions, conducting experiments, and fully absorbing knowledge. In chasing flexibility and employability, the trimester model often neglected that fundamental truth.

Mental health has a deadline too

Students didn’t just struggle with coursework—they raced against time. “I actually like the intensity, but it’s exhausting,“said a first-year undergraduate student. Her words echo a broader sentiment across campus. Many students force themselves to keep up with continuous evaluations, often sacrificing sleep, social skills, and emotional stability.

Still, glimpses of balance remain. On a sunny afternoon, students can be seen playing soccer on the university’s main field.

To be fair, not all students found the trimester model overwhelming. “Until now, I have never experienced burnout or insufficient breaks,” said Hannah Jiang, a postgraduate student. “I even added a summer term to help me study more so that I can finish my studies more quickly.” For outstanding and goal-driven students, this model offers an opportunity to accelerate their academic path and enter the workplace earlier.

But these cases appear to be the exception rather than the norm. While a small number thrived under pressure, a much larger group struggled to keep up.

Research in Higher Education has found that increasing the course load per semester is positively correlated with students’ academic performance. However, an excessively high course load may lead to a reduction in the time spent on each course, thereby having a negative impact on performance. In the case of UNSW, the promise of intensity may have come at the expense of long-term well-being and academic depth.

Misaligned with real-world opportunities

The trimester system often disconnects students from the recruitment cycle in the real world. Most postgraduate and internship programs in Australia and around the world follow a recruitment plan of once or twice a year. This means that students on a trimester calendar often find themselves applying for positions in the middle of their studies or during periods of heavy assessments.

Hannah Jiang said, “After changing to a two-semester system, the vacation time is divided into summer and winter, which is beneficial for students to find jobs.”

This mismatch not only limited students’ ability to pursue valuable internships but also affected their competitiveness after graduation. As the time to gain meaningful work experience is getting less and less, some people find that they graduated with good grades but weaker resumes – employers are increasingly noticing this imbalance.

Semester return: A sign of listening?

Facing years of mounting criticism, UNSW finally responded. In April 2025, the university announced plans to phase out the trimester system by 2028.

This decision was made after an internal review and extensive student consultations, highlighting the widespread dissatisfaction with the tight schedule. By resuming the two-semester model, the University of New South Wales seems to recognize the need to prioritize the well-being of students.

While the reform is not a panacea—issues like class size, workload distribution, and course quality still warrant attention. “The course duration is extended, and it is possible that the time for students to complete their studies will also increase,” said Hannah Jiang.

The return to semesters may not solve every problem overnight, but it represents a meaningful step towards a more student-centered higher education model.

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments, or cast your vote and let us know where you stand!

Be the first to comment