THE INVISIBLE BURDEN WEIGHING ON AUSTRALIA’S 700,000 INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS IS BECOMING IMPOSSIBLE TO IGNORE

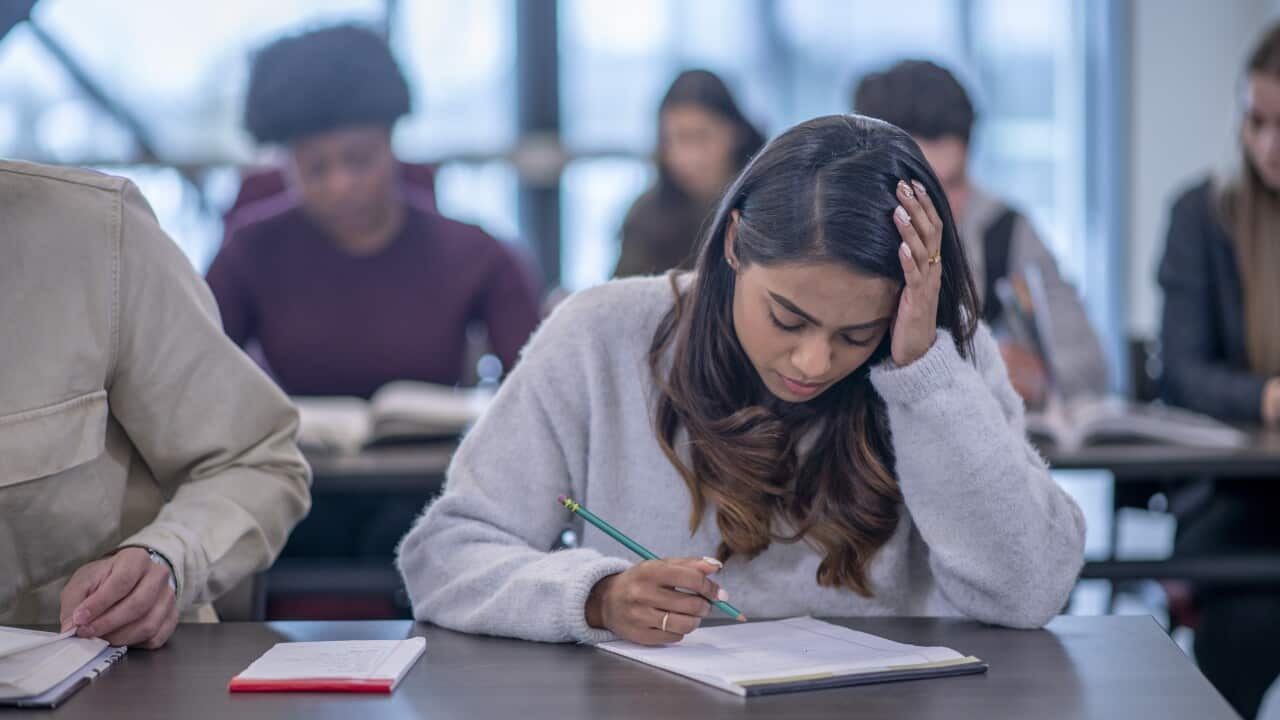

Luna sits in a Sydney park, explaining how she has learned to “hug trees” when anxiety overwhelms her. Just hours away, another international student lies awake for the third consecutive night, frustrated that even meeting the psychiatric has not solved their chronic insomnia. These contrasting stories illuminate a complex truth: Australia’s international student mental health crisis is not one-size-fits-all, and neither are the solutions.

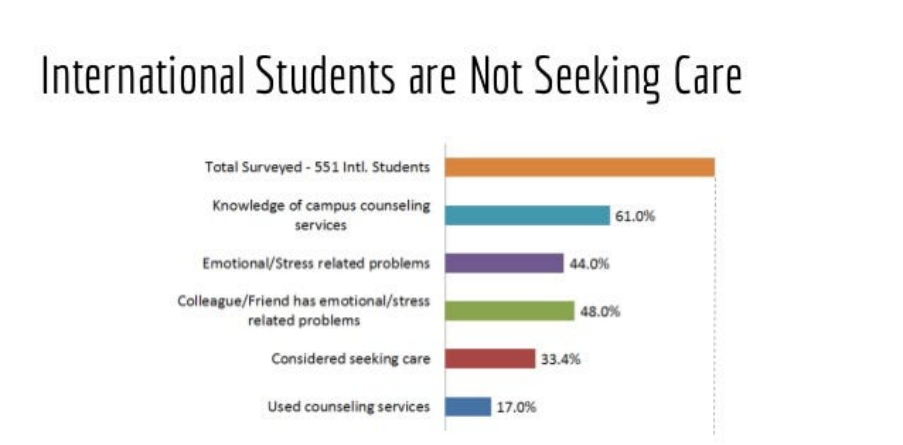

As Australia welcomes record numbers of international students over 713,144 in 2024. The mental health challenges they face have reached crisis proportions. Recent studies suggests that nearly one in four international students experience significant psychological distress, and these rates are higher than their local counterparts. What we need to see is behind these statistics lies a more concerning reality: many students are struggling in silence, caught in the web of cultural barriers and inadequate systemic support systems preventing them from seeking appropriate help.

International student shares her experiences

The challenges of international students extend far beyond academic pressure or sense of homesickness. Through our recent interviews conducting for this story, we identified a pattern of issues that is grappling these students, which is terms of as “invisible burden”- the factors leading to negative mental health among these students, which often goes unrecognised or addressed effectively by the universities and student support services.

Luna, an international student who moved to Sydney for studies explains- “The first few months I was in a kinda depressed and anxious mental state”. Her experience pinpoints how basic environmental factors like weather and even lifestyle changes can dramatically impact their mental well-being. While Luna has been able to find a stability in life through nature-based coping mechanism and maintaining constant connection with friends back home, her initial time in Sydney is marked with social anxiety and overwhelming emotions.

This is in sharp contrast to the experiences of the Virginia- other student we interviewed. For this student, housing issue became the source of mental health deterioration. “The first apartment in the City is very noisy, and I have insomnia; it is a really bad time to suffer,” she explains. For this sleep, unlike Luna, the lack of sleep has a rippling effect- impacting her mental health, the academic performance and overall quality of life.

Perhaps what we found most concerning is how our traditional mental health systems are failing these international students. The second student’s experience with psychiatrist further reveals a fundamental disconnect between need and availability of resources. “I do see the psychiatrist, I don’t think it can help with my insomnia, cause they are just saying logical things, I bet they never had real insomnia before,” she says. The frustration can be seen extending to the access of appropriate medications, with student expressing desperation over doctor’s restrictive prescribing practices, She says, “”Give me enough prescription for my sleeping pill, doctors, please stop against sleeping pills, it just makes everything worse, destroys people’s lives by simply saying no.” These experiences suggests that the current mental health services are not adequate to understand and address the specific challenges of the international students.

When questioned about the support from the university, the responses expose disconcerting awareness gap. While Luna admits; “Tbh I don’t know, didn’t pay attention on this,” Virginia accepts that efforts are being made but are they effective: “Well, I think they tried their best. Even doctors cannot help me with the insomnia, how could school help then?”

This disconnection between available services and student awareness—or trust in their effectiveness—suggests universities need to fundamentally rethink their approach. At times, students are not just unaware of the available services, they are hesitant to seek support for their needs.

The urge to keep up with the appearances adds another degree of complexity in the situation. Even Luna, who has been able to develop coping mechanisms for her mental health admits to have hidden her feeling in social situations: “Few times I would say, especially when I was in a group activities… I was in a bad mood that’s when I have to hide it cause I don’t want to make my friends feel uncomfortable.”

This social hiding adds to their psychological distress and makes it rather challenging to accurately assess the scale of the issue. Students who are struggling to private are compelled to show success and adaptability, which further isolates them from getting the right support networks.

The student’s suggestions indicate the need for more innovative and culturally responsive mental health support. Luna’s request for “meditation course or activities abt connecting with natures” demonstrates the need for more holistic approaches to strong mental health rather than mere crisis intervention. Her advice to future international student’s is to “think positive, try not to over thinking… touch some grass like go to a quiet garden or park, maybe hug trees”, stresses on the need for more nature based mental health mechanisms that should be made accessible by the universities support systems.

The stark differences in experiences of these students reveals the need for adopting multiple approaches to address and extend support for the mental health of the international students. While some students thrive with nature-based interventions and peer supports, others need immediate medical support to address conditions like insomnia. Universities must acknowledge the differences in the state of the students and move beyond “one-size-fits-all” mental health support, and look towards offering more personalised support system,

The second student’s suggestion hit the bull-eye of the solution: “If you feel sick, ask for help. If the person doesn’t offer you help, ask someone else.” However, for this to work, universities must ensure “some help” always exists for these students, there needs to multiple pathways to avail support services.

With international education system contributing significantly to the Australian economy, mental health crisis extends beyond humanitarian issue that should be addressed- it becomes an economic and country’s reputation requirement. Students who struggle silently, fail academically, or return home early represent not just personal tragedies but systemic failures.

The voices of students like Luna and others reveal that solutions exist, but they require listening to student experiences rather than imposing predetermined support models. As Australia continues to welcome international students, breaking the silence around their mental health struggles becomes not just compassionate policy, but essential for the sustainability of international education itself.

The crisis is real, but so is the resilience of these students. The question now is whether Australia’s institutions will match their adaptability with equally innovative, responsive support systems.

Be the first to comment