During the 2025 Federal Election, several politicians publicly accused international students of taking up local housing resources, including Opposition Leader Peter Dutton. He has advocated for reducing the number of international student visas to alleviate pressure on rental housing. This signals that overseas students are no longer participants but pawns in political games and election campaigning.

Accusation without evidence

In April 2025, Coalition education spokesperson Sarah Henderson told the ABC that reducing international student numbers was necessary to free up housing for young Australians.

“Our top priority is to help Australians access and secure housing,” he said.

However, research from the University of South Australia has revealed that international students are being ‘demonised’ and unfairly blamed for the rental crisis.

The study looked at data from government departments and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) at 76 points in time between 2017 and 2024, and concluded that the correlation between the number of international students and the cost of rent was random.

That is to say, the hypothesis that an increase in the number of international students will make it harder for everyone to find accommodation is not valid.

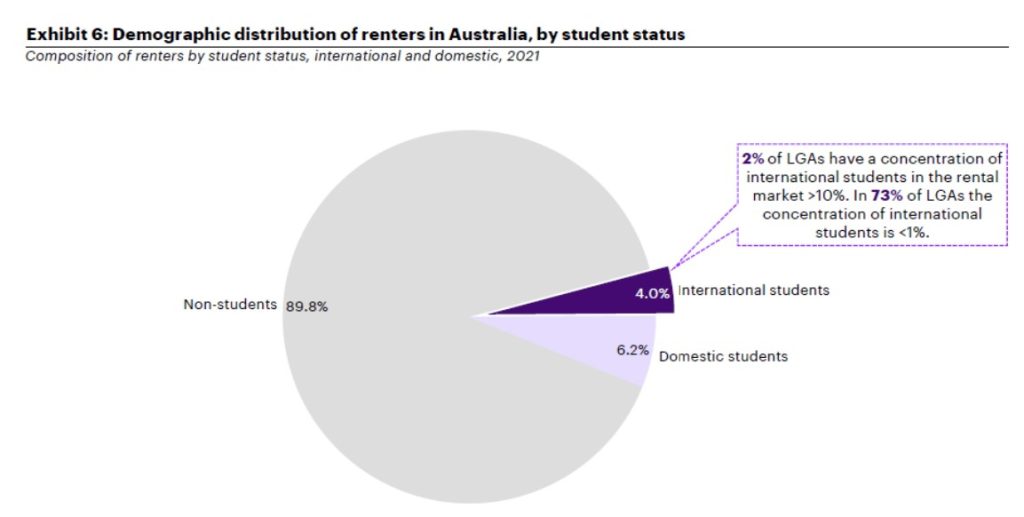

The Student Accommodation Council report also shows that international students are not the driver of the housing crisis, accounting for only 4 per cent of the Australian rental market.

Gareth Bryant, Chair of Political Economy at the University of Sydney and Economist in Residence at the Sydney Policy Laboratory, giving his opinion on this issue.

“There is no evidence that international students are creating a massive housing crisis. In fact, I’d say the opposite that governments and universities should be doing more to help international students access safe and good housing,” he said.

Losing in the rental race

Some politicians claim that the return of students after the pandemic has caused rental shortages and rising rents. But he fact is that international students are often in a disadvantaged position in the rental market.

Xiaobei Liu, a real estate agent in Sydney, said that many local landlords prefer locals or people with jobs.

“They don’t want to rent to international students. Because they think students don’t have stable income or might make noise,” she said.

The real responsibility

Blaming international students for a longstanding problem is irrational. The real culprits to be held accountable are the government that lacks systematic planning, and the over-commercialised higher education in Australia.

Construction trades workers were found to be in national shortage, which means that even if land and finance are available, the lack of sufficient labour will make housing construction impossible.

Government inefficiencies in approving urban planning and housing development have also further intensified the pressure on housing supply. NSW aims to deliver 377,000 new homes over 5 years by July 2029 under the National Housing Accord to address the housing crisis and meet Housing Accord targets.

However, the Housing Taskforce team, made up of staff from the state agencies, has completed approvals for only 30,000 new homes in six months, falling far behind the actual demand, which has also contributed to the tight housing availability in NSW.

On the other hand, universities are equally to blame. For many international students, student accommodation is their first choice of housing, but that is not ideal in Australia.

Qianhui Zhu, an international student from China, applied for student accommodation at the University of Sydney months before she arrived in Australia. However, she was still on a waiting list after the semester began.

“In China, students don’t need to rent a room because almost all schools provide dormitories,” she said.

In Australia, the occupancy rate of student accommodation is about 6 per cent, or one bed for every 15 university students. There is a 25,000 to 30,000 student bed shortage in Sydney Inner west and CBD, which leaves USYD and UTS students without suitable housing alternatives.

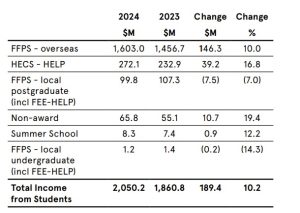

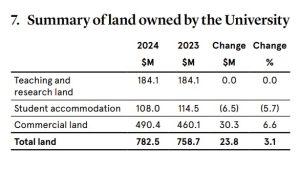

Take USYD as an example, the Annual Financial Report 2024 shows that tuition fees contributed by Full Fee-Paying Students, at A$1,603 million, were the primary driver of student revenue growth, with an annual increase of A$146 million.

However, its investment in student accommodation is shrinking, with data showing that the asset value of student accommodation sites has fallen by 5.7 per cent. In comparison, commercial sites have increased by 6.6 per cent.

This trend is not accidental. As early as 2020, the University of Sydney has closed its International House, an accommodation program for international students, and there has been no equivalent replacement.

This implies that the university is not prioritising the investment of resources to improve the residential struggles of its international students, but simply sees international students as a cash cow and a way to make more money.

Blaming a long-term problem on students who do not have the right to vote and political representation does not address the issue of housing affordability. Nor does it help this group interact with local Australian communities.

The real solution lies in governments and universities actively taking responsibility to drive meaningful reforms in housing policy and providing better support for overseas students.

What policy responses do you think are most urgently needed? Leave your thoughts in the comments.

Be the first to comment