A Routine Day Turns into a Scam

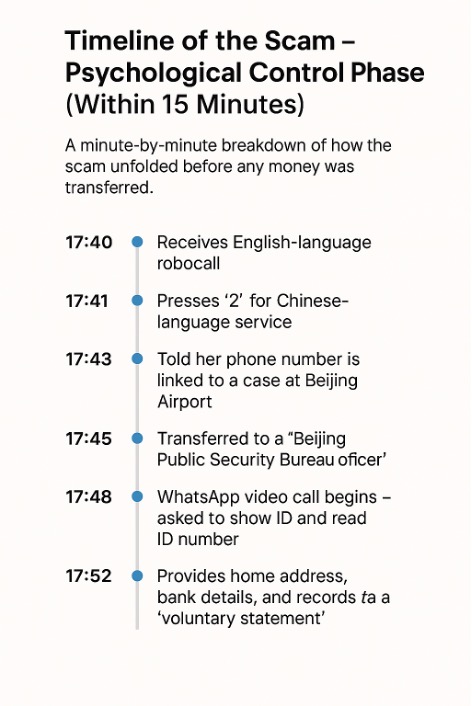

In early March, less than a week after arriving in Sydney, Willow Wang, a 23-year-old Chinese student, was about to take the bus home after shopping in the city center. At that moment, an unfamiliar caller with a local Australian number popped up. When the call came through, it was a standard English voice announcement that her mobile phone number would be deactivated within two hours, and it gave the exact international area code she was using.

“If you need Chinese service, please press 2,” the voice prompt concluded. For Willow, a newcomer to a foreign country, the familiarity of the language was a welcome relief. Without thinking, she pressed the number and walked into a scam.

Fake Police, Real Fear

After connecting to the “Chinese customer service”, a person claiming to be a communications company staff told Willow that others had fraudulently used her mobile phone number to register a new card at the Beijing Capital International Airport, and thousands of illegal messages had been sent.

He then took a different tack, saying that this was no longer a normal shutdown, but a criminal case of ‘suspected transnational fraud’.

“I was a bit skeptical, but then he started calling me by my full Chinese name, my date of birth, and even told me which bank card I was using, and I really panicked,” Willow said.

Immediately after, the caller claimed she needed to “cooperate with a police investigation” and was “transferred” to a man who introduced himself as an officer from the Beijing Public Security Bureau. He sent a video call request via WhatsApp, asking Willow to turn on her camera and complete a so-called “remote statement.”

He asked her to show the front and back of her ID card, read out her ID number, record a video stating her “voluntary cooperation with the investigation,” and then provide additional details, including her current address, bank branch, and mobile service provider.

From Hesitation to Loss

After the video call, the caller told Willow that her identity had been “provisionally confirmed,” but the case was serious. She was instructed to immediately transfer all her funds into a “security account supervised by the police” for further investigation into potential money laundering.

“I was just panicking. They kept calling and sending me screenshots to say they had filed a case,” she recalls. “I was so scared and didn’t know what to do.”

After ten straight minutes of high-pressure calls, she opened her banking app and, using the account details provided, completed the transfer. She then sent a screenshot to the scammer “for the record.”

Silence, Shame, and Realisation

It was only when she came across a nearly identical story on Xiaohongshu that she completely realized she had indeed been scammed. She immediately called her bank to report the card as lost and went to the branch in person to freeze the account, but the two thousand Australian dollars she had transferred were already long gone.

However, Willow didn’t call the police or confide in the school or any of her friends. “I really couldn’t say anything,” she said. “On one hand, I felt ashamed and on the other hand, I didn’t know how to talk about the whole thing in English.” It wasn’t until a week later that she brought up the incident in a video call with her mother.

“My biggest fear at the time was not the money, but whether they would take my ID, voice, and face data and use it again for something else,” she says. “That aftermath is still with me to this day — my heart races when I see strange phone calls.”

Willow is not alone. The ripple effects of identity breaches are growing.

According to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) Targeting Scam Report 2024, released in March 2025, the total number of fraud reports in Australia dropped by 25.9 per cent compared to the previous year. However, losses linked to identity theft are rising sharply, with IDCARE reporting a 40.1 per cent increase.

In addition, according to the ACCC Telecommunications Fraud Report for the first quarter of 2025, the international student community has become a “high-frequency target group”, with more than 750 reports of international students being scammed in the first three months alone and an average loss of more than $4,200 per case.

Information That’s Hard to Find

The Chinese Embassy in Australia has also issued several reminders to be wary of telecoms online scams. While the NSW police, the University of Sydney, and the Australian Federal Department of Education have also issued notices, most of the content is hidden in deep links on official English web pages, making it extremely difficult for newly arrived international students.

What Needs to Change

In retrospect, Willow wishes more than anything that she had spoken up and asked for help in the first place, rather than burying it all in silence. “Being lied to is not something to be ashamed of,” she says.

Murray Print, Professor of Political Education at the University of Sydney, who specialises in civic education and cross-cultural institutional understanding, notes that “international students in any country may feel a degree of institutional discomfort, especially when language barriers are involved.”

“What they really need,” Professor Print adds, “is a year-long cultural onboarding process.”

For the higher education system, staying “safe” shouldn’t stop at sending an email or posting a static webpage in English. It should be about making information understandable and visible at critical moments.

“We don’t come thousands of kilometers from home with a firewall of information,” Willow adds. “If you can’t communicate even the most basic security, then trust is very hard to build.”

Be the first to comment